Almond, Sweet – (Prunus dulcis)

Almond, Sweet – (Prunus dulcis)

Image by RÜŞTÜ BOZKUŞ from Pixabay

Sweet Almond Tree (Prunus dulcis) - Botanical Profile, History, Benefits & Uses

Early in the year, around Valentine’s Day, almond trees sense the approaching spring and burst into bloom. Their graceful branches become adorned with a profusion of delicate pinkish-white flowers with dark centres—an enchanting display of nature’s divine grace.

Image by Brigitte Werner from Pixabay

Image by Fernando Espí from Pixabay

Sweet Almond Tree – Habitat, Distribution and Climate

Sweet almond trees are native to the arid mountains of Central and Southwest Asia, ranging from the Tien Shan Mountains in western China to Turkestan, Kurdistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq—regions where wild relatives still grow.

They thrive in semi-arid Mediterranean climates with mild, moist winters and hot summers. The trees start to produce their velvety fruits within 3 to 6 years. (Gorawala, 2022)

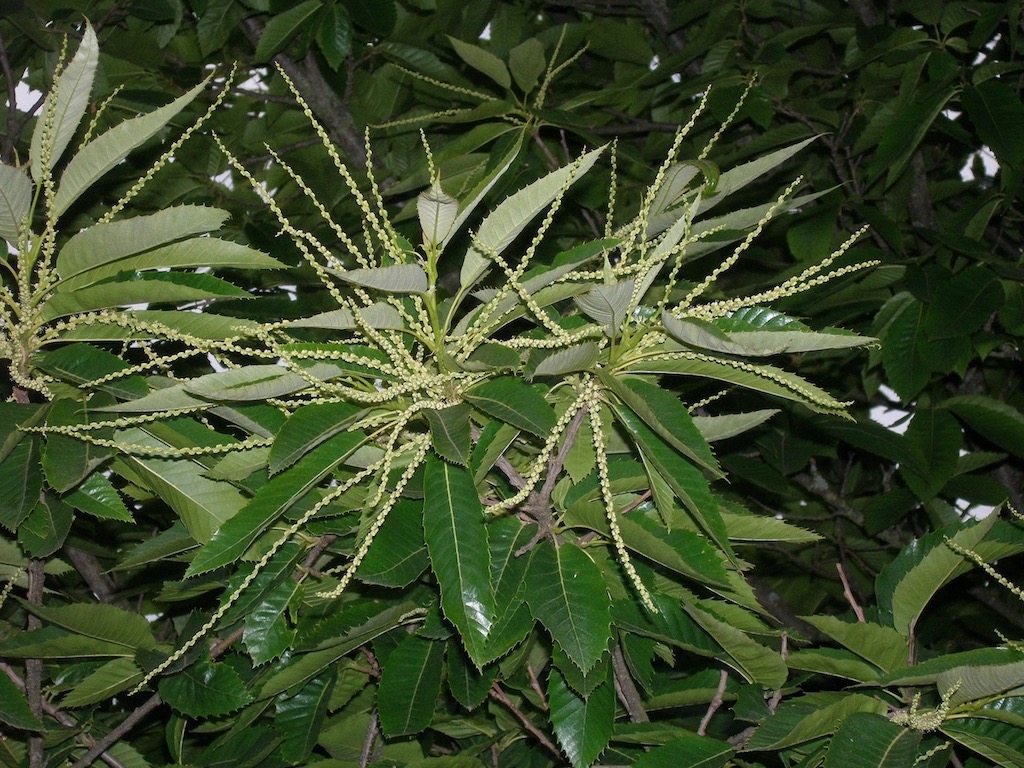

Botanical Description

The sweet almond tree is a slow-growing, deciduous tree in the Prunus genus, closely related to apricots, peaches, and plums.

The trees can reach a height of 3-5 m. Their leaves resemble peach leaves: elongated, lanceolate and slightly serrated. The flowers, which in the warmer regions of the Mediterranean Basin can appear as early as the end of January, are delicate and beautiful 5-petaled pinkish-white blossoms with a darker centre and a splatter of stamens. Almond trees are self-incompatible and rely on honeybees for fertilisation. (Almond | Definition, Cultivation, Types, Nutrition, Uses, Nut, & Facts | Britannica, 2025)

Like its relatives, it produces a fruit containing a hard, woody stone that protects an oil-rich kernel. But unlike those fruity relatives, the endocarp or fleshy part is woody and offers no nourishment. The edible part is only the embryonic seed itself. The trees begin producing velvety fruits within 3 to 6 years. As the seeds mature, the outer skin splits open, exposing the woody ’nut’ inside. Technically, the almonds are drupes rather than true nuts. (Gorawala, 2022) Interestingly, the kernels of wild almond trees—and those of their botanical cousins—contain amygdalin, a cyanogenic glycoside that is highly toxic. (Jaszczak-Wilke et al., 2021)

The mystery of how sweet almonds were domesticated and lost this deadly poison remains unsolved.

Almonds’ Ancient Origin

Archaeological evidence suggests almonds were cultivated in the Middle East as early as the Bronze Age, but their importance as a major food source dates much further back in time. Remains of nut shells near pitted hammers and anvils found at Gesher Benot Ya’aqov (Israel) dated to the Pleistocene Era (780 000 b.c.e.) include the shells of wild almonds. But domesticated almonds are not recorded before the late Bronze Age (3000-2000 b.c.e.), at the dawn of agriculture in the Near East.

Almonds were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (1325 b.c.e) and at Deir-el-Medina, a workmen’s village and home of the artisans involved in building the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th-20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (1550-1080 b.c.e.). Other significant archaeological sites that have yielded prehistoric remains of almonds are found in Crete: at the Neolithic level, underneath the palace at Knossos, and in the storerooms at Hagia Triada, a site associated with the Minoan culture that thrived during the Bronze Age.

Almonds in Biblical Times

When the Arabs conquered North Africa, they introduced Almonds to Tunisia and Morocco and Greek and Arab traders spread them throughout the Mediterranean along ancient trade routes. (Casas-Agustench et al., 2011)

Almonds and their precious oil were well-known in classical Greek and Roman times, long before the Christian era.

The Bible frequently refers to almonds and notes that they are one of the best fruit trees of the land of Canaan. Almonds, known as ‘shakad’ in Hebrew, carry great cultural and spiritual significance in the Jewish tradition. (Grieve, 1998)

‘Shaka’ means to wake, watch and be alert and vigilant. (Šāqaḏ Meaning – Hebrew Lexicon | Old Testament (KJV), n.d.) Twigs of almond blossom are still used to adorn the synagogues at important festivals. According to Mrs. Grieves, Aaron’s rod was an almond twig, and the nuts were chosen to decorate the golden candlestick used in the tabernacle. (Grieve, 1998)

Almonds from Roman Times to the Middle Ages

Almonds spread to northern Europe and even to the British Isles very early on, probably with the Romans, but were not cultivated there until the 16th century. (Grieve, 1998). They became an important item of trade in Europe and feature strongly in medieval recipes. In 1372, the Queen of France, Jeanne d’Evreux, was reported to have a hoard of 500 lb. of almonds in her storage. (Grieve, 1998)

By the Middle Ages, almonds and even almond milk were hugely popular, not just in southern Europe, where almonds grow, but all over Europe and the UK. Despite their high price tag, they feature in dozens of recipes. Even almond milk, far from being a modern invention, was probably invented in the context of religious taboos at Lent, when animal products were banned from the table.

At any rate, animal milk was reserved for children and for making cheese, so almond butter and milk readily replaced the dairy option – judging by the prolific mentions in medieval cookbooks. (Clarke, 500)

Almonds Spread to the Americas

Almonds were introduced to the Americas by Spanish Franciscan monks, first in Mexico and later to California, between 1769 and 1823. But when they abandoned their mission, the almond orchards died. The venture was revived in 1854, soon after California became a state of the Union. It did not take long for growers to learn about the specific needs of this valuable crop. Californian almonds are practically all descendants of the French varieties, Nonpareil, Non Plus Ultra and IXL and are grown successfully in the Central Valley. (History Of Almond Production, n.d.)

Image by Maria Teresa Martínez from Pixabay

Almonds as a Commercial Crop and its Environmental Implications

Today, the leading almond-producing countries include the United States, China, Australia, Spain, and other Mediterranean regions. (Gorawala, 2022)

Commercial almond production is big business. Vast orchards cover thousands of hectares of almond trees. Because of climate change, prolonged droughts and pressure on water resources production have become challenging, making trees more vulnerable to pests, which increases the need for pesticides and herbicides, harming not only their intended victims but also the honey bees needed to pollinate the flowers. Of course, it does not stop there but continues through the food chain, affecting all insect-eating animals, especially birds. Last but not least, farmworkers, exposed to the Agro-poisons, and the local population, are affected not only by direct exposure but also via the groundwater, where herbicides and pesticides inevitably end up. Bees, stressed by Agro-chemicals and transport conditions (they are often ferried across the country for thousands of miles), are succumbing to colony collapse syndrome (CCD), a potentially existential threat to both, bees and their keepers (almost 3 million hives are rented to pollinate the Californian orchards alone). And, since almond trees are self-incompatible, they depend on bees for their survival, too.(Almond | Definition, Cultivation, Types, Nutrition, Uses, Nut, & Facts | Britannica, 2025), (An Unhealthy Alliance between Almonds and Honeybees, 2019)

Modern Research and Alternative Cultivation Models

Agricultural research teams are working to develop hybrids that are not dependent on bees, but these new varieties are not yet ready for commercialisation.

Traditional orchards in Europe and the Middle East are much smaller and family-owned. Harvest is frequently still done by hand. The commercial operations of the Agro-industry employ mechanical nut shakers to speed up the harvest. (Almond | Definition, Cultivation, Types, Nutrition, Uses, Nut, & Facts | Britannica, 2025)

There is a shadow side to almonds’ popularity. With the recent trend to replace dairy milk and butter with plant-based alternatives like almond milk, the pressure on the environment has risen exponentially. Almond milk is not an animal product, but it is not cruelty-free. Almond cultivation relies on honeybees for pollination. Commercially grown, non-organic almonds and their derivative products, such as almond milk, butter, marzipan and almond flour, are not sustainable choices.

Almonds in Regenerative Agricultural

There is hope. Some growers are adopting regenerative practices to lessen the industry’s environmental impact. They report higher yields while using fewer resources, an increase in organic matter, improved soil health and structure, and reduced water consumption. The results are healthier trees producing more resilient nuts – and happy bees.

Sweet Almond Nutritional Profile – Vitamins, Minerals and Health Benefits

Hippocrates (460-370 b.c.e.), the ‘father of medicine’, recorded the properties of Almonds in the ‘Corpus Hippocraticum’, describing them as ‘burning, but nutritious’. The Ancient Greeks used a categorisation system similar to the Ayurvedic teachings, the ‘humoural system’ that classified substances according to their essential nature and the elements. In this system, oily substances were regarded as fiery, hot and dry.

Ayurveda and Unani Medicine

In Ayurveda and Unani medicine, almonds are highly valued for their health benefits. They are believed to enhance brain function, improve skin health, and boost overall vitality, mirroring the cultural significance of almonds as symbols of wellness and nourishment.

Hildgegard von Bingen

Hildegard von Bingen also praised almonds highly. She suggested that those with a bad skin complexion and an ‘empty head’ would benefit from eating almonds regularly. (Hertzka & Strehlow, 2002)

Almonds are indeed highly beneficial. They contain many micro- and macronutrients, essential fatty acids, amino acids, vitamins and minerals. Studies have shown that despite their rich oil content of about 50%, they can modulate serum glucose, lipid and uric acid levels. They help to regulate body weight and protect against diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases. Recent research also shows that almonds have a prebiotic effect, supporting beneficial gut-flora and protecting the digestive system against diseases like IBS. (Barreca et al., 2020)

Image by PublicDomainPictures from Pixabay

Almond Cuisine: Sweet and Savoury Dishes

Almonds are a delicious and healthy nuts, partly because of their nutrient-rich oil. The highly beneficial polyphenols, associated with almond’s prebiotic effect, are found in the skin. It is better not to blanch the almonds for maximum benefit, but it depends on the dish. Sometimes a finer texture is preferred. Almond skins are sometimes used as fibre in supplements or food additives.

Almond oil is relatively stable, and stored properly, it keeps for about one year. Organic almond oil is edible and very nutritious. The nuts themselves deliver additional benefits. They can be eaten raw, roasted or enjoyed as a creamy spread known as almond butter.

As we have seen, almond milk and butter were invented in the Middle Ages. Such products are currently experiencing a major renaissance, especially in the whole food sector. But apart from the recent almond milk revival, the nuts themselves are highly versatile and can be used in both, sweet and savoury dishes.

Sweet Almond dishes

Countless cakes, tarts, biscuits and puddings are made with almonds – but most importantly, they are the key ingredient in marzipan. Simple, but delicious, sugar or chocolate-coated almonds or candied almonds are traditional Christmas treats. In Mediterranean countries, almonds feature most prominently in Easter baking. Colomba di Pasqua is a traditional Italian Easter cake featuring almonds, and pastries known as Jesuits or Jesuits’ hats, triangular flaky puff pastry filled with frangipane and topped with flaked almonds, is popular in France. In India, Badam Kulfi, a type of ice cream, is made with condensed milk and almonds.

Savoury Almond dishes

Flaked almonds are used for decoration, but entire nuts or ground nuts are often incorporated as a more substantive ingredient. They are often included in Kormas (Indian and Pakistani cuisine), or can be part of the nut mixture of nut loaves in vegetarian cooking. Hickory smoked or roasted almonds make a healthy and nutritious snack and almond flour can be used in baking as a gluten-free alternative, to thicken sauces and stews. But, because almonds do not contain gluten, they cannot simply be exchanged 1:1 for regular wheat flour.

In Andalucia, Ajoblanco, a cold soup made with ground almonds, left-over bread, garlic, water and olive oil is a popular dish in the summer. Almond meal (more unblanched, coarsely ground almonds) makes an excellent alternative to bread crumbs or can be used in a half-and-half blend.

There are hundreds of recipes out there. A selection will be posted in recipe section of sacredearth.com soon.

Caution:

People susceptible to nut allergies should abstain from almonds and almond products. If you are allergic to peaches, you are more likely to react to almonds. Cross-reactivity with other tree nuts is also common. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and can even be fatal. Pollen allergy is only an issue in almond-producing regions. (Almond Allergy, n.d.)

Mould is a risk, since almonds can be attacked by aflatoxin-producing moulds, which are highly toxic and considered a potent carcinogen implicated in causing liver cancer. The EU has strict food testing standards and tests shipments of almonds both within the Union and from abroad.

(Aflatoxins in Food | EFSA, 2021)

Almond Oil – Extraction Method Matters

Almond oil is edible, but only food-grade organic almond oil is recommended for culinary uses. Most conventional almond oil is extracted using solvents like hexane, removing much of its nutritional and therapeutic value. In contrast, organic, virgin cold-pressed almond oil is rich in essential nutrients, but this method produces lower yields, making it more expensive. (Roncero et al., 2016)

Cosmetic Properties

Almond oil is a prized ingredient in natural cosmetics due to its:

- Light texture

- High stability from monounsaturated oleic acid

- Smooth application with good slippage

- Suitability for sensitive skin around the eyes

Almond Oil Uses – Skin, Hair Care and Therapeutic Applications

Nutrient-rich Almond oil is widely used in skin care preparations and as a base oil for therapeutic massages. Rich in vitamin E, potassium, magnesium, calcium, and zinc, it nourishes the skin and prevents damage caused by free radicals. Almond oil is recommended for sensitive and mature skin.

Pure, unrefined cold-pressed almond oil has a fine texture and a subtle, nutty fragrance. While relatively light, it does not immediately absorb into the skin, making it an excellent choice for massage oils. Its high proportion of monounsaturated oleic acid ensures oxidation resistance when stored properly. (Kusmirek, 2002)

Almond Oil Benefits and Uses

Traditional medical systems in China, India, Greece, and Persia valued almond oil for its remarkable moisturising and skin-care properties. It has been used to:

- Prevent scarring

- Soothe sun-damaged skin

- Smooth mature skin

- Reduce puffiness and wrinkles around the eyes

- Relieve itching

- Treat irritable skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis, and dry, flaky skin (Ahmad, 2010)

Natural Body Care Applications

Almond oil’s soothing and emollient qualities make it suitable for all skin types. It is among the most widely used and sought-after base oils for natural cosmetics. Mixed with oat bran or ground almonds, it creates a nourishing and cleansing body scrub. (Bly, 2019) Additionally, it is a valuable additive in soap-making, contributing to a creamy, nourishing lather. Other uses include:

- Body lotions and night creams

- Skin-repair formulation

- Soothing anti-inflammatory ointments

- Body butters and lip balms

- Hair-repair oil treatments

- After-sun care lotions

- Aromatherapy massage blends (Kusmirek, 2002)

Image by Annette Meyer from Pixabay

Mythology

The beautiful, endearing almond tree features in many ancient stories, folklore and mythology, especially in Southern Europe and the Levant. It symbolises rebirth at the awakening of spring, undying hope, abundance, generosity, beauty, love, devotion, and inspiration. (Altman, 2000) In Greek mythology, the almond tree is associated with Jupiter and Gaia, Agdistis and Attis (Atsma, 2000) and is also linked to the tragic story of Phyllis and Demophon.

References

- Aflatoxins in food | EFSA. (2021, December 21). https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/aflatoxins-food

- Ahmad, Z. (2010). The uses and properties of almond oil. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 16(1), 10–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.06.015

- Almond | Definition, Cultivation, Types, Nutrition, Uses, Nut, & Facts | Britannica. (2025, February 24). https://www.britannica.com/plant/almond

- Almond Allergy. (n.d.). Retrieved 4 March 2025, from https://www.food-info.net/uk/intol/almond.htm

- Altman, N. (2000). Sacred trees: Spirituality, wisdom & well-being. Sterling Pub.

- An unhealthy alliance between almonds and honeybees. (2019, June 20). Food and Environment Reporting Network. https://thefern.org/2019/06/an-unhealthy-alliance-between-almonds-and-honeybees/

- Barreca, D., Nabavi, S. M., Sureda, A., Rasekhian, M., Raciti, R., Silva, A. S., Annunziata, G., Arnone, A., Tenore, G. C., Süntar, İ., & Mandalari, G. (2020). Almonds (Prunus Dulcis Mill. D. A. Webb): A Source of Nutrients and Health-Promoting Compounds. Nutrients, 12(3), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030672

- Casas-Agustench, P., Salas-Huetos, A., & Salas-Salvadó, J. (2011). Mediterranean nuts: Origins, ancient medicinal benefits and symbolism. Public Health Nutrition, 14(12A), 2296–2301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980011002540

- Clarke, J. (500, 49:00). In the Middle Ages, the Upper Class Went Nuts for Almond Milk. Atlas Obscura. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/almond-milk-obsession-origins-middle-ages

- Gorawala, P. (2022). Agricultural Research Updates. Volume 40 (1st ed). Nova Science Publishers, Incorporated.

- Grieve, M. (1998). A modern herbal: The medicinal, culinary, cosmetic and economic properties, cultivation and folklore of herbs, grasses, fungi, shrubs & trees, with all their modern scientific uses. Tiger Books internat.

- Hertzka, G., & Strehlow, W. (2002). Die Küchengeheimnisse der Hildegard-Medizin: Ratschläge und Erkenntnisse der heiligen Hildegard von Bingen über die Heilkraft unserer Nahrungsmittel (12. Aufl). Bauer.

- History Of Almond Production. (n.d.). Retrieved 3 March 2025, from https://wholesalenutsanddriedfruit.com/history-of-almond-production/

- Jaszczak-Wilke, E., Polkowska, Ż., Koprowski, M., Owsianik, K., Mitchell, A. E., & Bałczewski, P. (2021). Amygdalin: Toxicity, Anticancer Activity and Analytical Procedures for Its Determination in Plant Seeds. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 26(8), 2253. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26082253

- Kusmirek, J. (2002). Liquid Sunshine—Vegetable Oils for Aromatherapy. Floramicus.

- šāqaḏ Meaning—Hebrew Lexicon | Old Testament (KJV). (n.d.). Retrieved 3 March 2025, from https://www.biblestudytools.com/lexicons/hebrew/kjv/shaqad.html