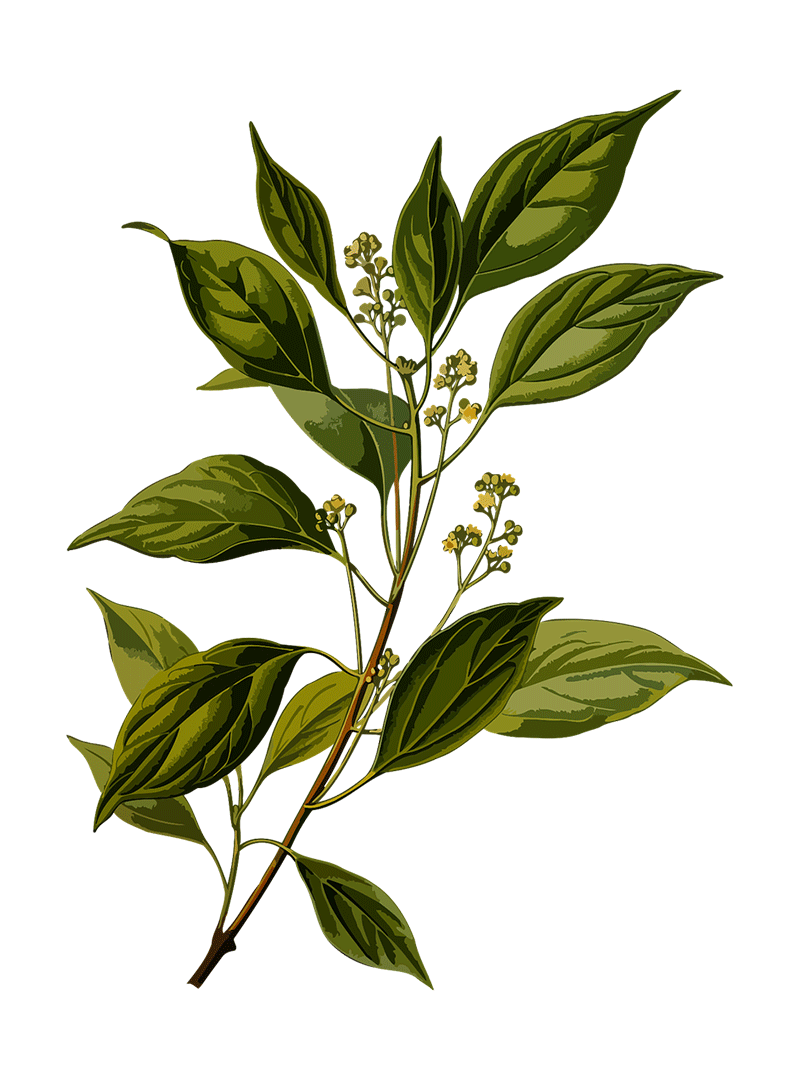

The Camphor Tree

Camphor constituent: essential oils

Parts used: essential oil, waxy crystalline flammable substance

Medicinal actions:

Used in ‘cold creams’ as an anti-aging ingredient. Stimulates the production of collagen and elastin.

Anti-inflammatory – applied to sore, inflamed skin (not on broken skin)

Pain relief for arthritic, or rheumatic pain

Antifungal – can be applied to toenail fungus. (Needs persistence. It can take up to 48 weeks before positive impact is noticed).

Decongestant and cough suppressant – evaporate in oil diffuser during the night

Antispasmodic – can be used to relieve muscle aches and pains, cramps, sprains

Anti-viral – used to treat infectious fevers such as typhoid, influenza, and pneumonia.

“ Medicinal Action and Uses—Camphor has a strong, penetrating, fragrant odour, a bitter, pungent taste, and is slightly cold to the touch like menthol leaves; locally it is an irritant, numbs the peripheral sensory nerves, and is slightly antiseptic; it is not readily absorbed by the mucous membrane, but is easily absorbed by the subcutaneous tissue- it combines in the body with glucuronic acid, and in this condition is voided by the urine. Experiments on frogs show a depressant action to the spinal column, no motor disturbance, but a slow increasing paralysis; in mankind it causes convulsions, from the effect it has on the motor tract of the brain; it stimulates the intellectual centres and prevents narcotic drugs taking effect, but in cases of nervous excitement it has a soothing and quieting result. Authorities vary as to its effect on blood pressure; some think it raises it, others take an opposite view; but it has been proved valuable as an excitant in cases of heart failure, whether due to diseases or as a result of infectious fevers, such as typhoid and pneumonia, not only in the latter case as a stimulant to circulation, but as preventing the growth of pneumococci. Camphor is used in medicine internally for its calming influence in hysteria, nervousness and neuralgia, and for serious diarrhoea, and externally as a counter-irritant in rheumatisms, sprains bronchitis, and in inflammatory conditions, and sometimes in conjunction with menthol and phenol for heart failure; “

Mrs. Grieves, A Modern Herbal

Camphor Tree – The Dragon’s Brain

The characteristic scent of Camphor is familiar to anyone who has had a close encounter with VapoRub, but few have ever seen the pure, white crystalline substance from which the scent derives. Still, fewer are aware that this mysterious substance is entirely natural and comes from a tree that is native to southern China, southern Japan, and Taiwan. The Camphor Tree (Cinnamomum camphora) is closely related to the Cinnamon Tree, (Cinnamomum zeylanicum), with which it is sometimes confused. However, the unmistakable scent of the leaves immediately reveals its true identity.

In China, Camphor is known as ‘long nao xiang’, ‘the dragon’s brain’, but it is unclear whether the name makes reference to its powerful brain-fog blasting effect, or whether the use of Camphor may originally have been the privilege of the emperor, who is often referred to as the (imperial) ‘dragon’.

Camphor trees can become very old – up to several hundred years, in fact. Such tree veterans are a majestic sight to behold. They can reach up to 40m in height and develop a truly massive base. One tree, recorded in the prefecture of Nagasaki, was recorded to measure a staggering 16 m of girth. Hardly surprising then, that the evergreen tree is seen as an icon of vitality and longevity.

In China, Japan and India Camphor trees are sacred. They are planted for protection near dwellings, temples, and monasteries, and Camphor is burnt as incense in purification rituals or in pujas. Its pure, bright and smokeless flame is seen as a representation of Shiva.

During the 13th century, while traveling through China, Marco Polo reported seeing ‘great forests where the trees are found that give camphor’. At that time, Camphor had already been introduced to Europe, along with other exotic spices such as Cinnamon, Pepper, Cardamom, and Wood-Aloes. But the Camphor tree itself was virtually unknown. The precious substances reached Europe via the Spice Route and first found its way to the spice markets north of the Alps during the 10th century.

However, it took several centuries more, until the latter half of the 17th century, for the first trees to be introduced to Europe. But then they took the eminent Botanical Gardens of Europe by storm: They were planted at the Botanical Gardens of Padua, Leiden, Dresden, and the Chelsea Physic Gardens. Many of them are still standing now. Their import to Europe has had no ill effect on the local environment, but in more favourable climatic conditions, Camphor trees have been known to spread prolifically. In some parts of Australia and the southern United States, they are now considered an invasive pest.

In the Orient, Camphor is highly valued and has a long tradition of medicinal and culinary use. It is mentioned in various Arab and Indian cookery books, and in India, it is an ingredient of the Betel quid, a popular chewing stimulant.

In the West Camphor is better known for its medicinal properties. It is valued for its antiseptic and cooling properties and its ability to relieve pain and swelling associated with inflammatory skin conditions, chilblains, burns, and anal fissures. It is also used as a counter-irritant and applied topically to painful arthritic or rheumatic joints.

Added to a steam inhalation Camphor can clear congestion of the lungs, bronchi and nasal passages. In the past, it was used internally as an antiseptic digestive aid. Thanks to Samuel Hahnemann, the ‘father of Homeopathic medicine’ it became a lifesaver during the outbreaks of Asiatic cholera in 1831/32 and 1848/49. Having received first-hand reports from Russian colleagues, he treated victims at frequent intervals with a homeopathic tincture of Camphor – apparently with great success. Even allopathic doctors admitted that it was about the only thing capable of halting the progress of this lethal disease when administered during the early stages.

Camphor is an antidote to Opium and recipes found in ancient Arab manuscripts often combine both substances to alleviate some of Opium’s negative effects. During the Victorian era, camphor became popular among members of the upper classes, particularly in the UK, the US and in Slovakia. It was combined with milk, alcohol or consumed in pill form as a stimulating recreational drug. The effective dose is very small and said to produce a warm, tingling skin sensation, a sense of mental clarity, or ‘a rush of thoughts chasing each other’, sometimes accompanied by euphoria.

However, the bad news is, that larger doses can produce quite unpleasant effects: confusion, giddiness, accelerated heart rate, headaches, and even death. Thus, many countries have regulated Camphor. Today, most commercially available Camphor is synthetically produced and not fit for internal use at all. It is regrettable that a beneficial and medicinally useful substance such as Camphor should be disgraced and forgotten, despite the eons of safe use, just because some people have overindulged in it – to their own detriment.

Caution: Only Camphor that is clearly labeled as edible may be taken internally, and then only in tiny doses. Quantities of more than 2g can be fatal to adults. The lethal dose for children and youths is significantly lower.

During pregnancy and lactation, it is advised to avoid camphor products altogether. Due to its toxicity at a low dose, it should also be kept away from children. Some people have reported contact dermatitis from handling Camphor.

#Ads

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases on Amazon and other affiliate sites.

The flowers are known as catkins. Both male and female flowers are present on the same tree, though they develop separately. The male flowers begin to develop in the summer, endure the winter and wait until the female flowers appear in spring. They court the wind as pollinator and distributor of their tiny winged seeds, which are so light that they may be carried for several hundred miles.

The flowers are known as catkins. Both male and female flowers are present on the same tree, though they develop separately. The male flowers begin to develop in the summer, endure the winter and wait until the female flowers appear in spring. They court the wind as pollinator and distributor of their tiny winged seeds, which are so light that they may be carried for several hundred miles.