Walnuts (Juglans regia)

It’s ‘nutty season’! (No, I don’t mean politics, in this case) I have was reminded of the fact by the intermittent popping noises coming from outside my window and by the mass of fuzzy hazelnut balls that are piling up on the front porch. These Turkish hazelnuts are plentiful, for sure, and easy to collect. But they are small and extremely tedious to crack. Thankfully, nature provides plentifully and these are not the only nut trees around. We also have some Walnut trees – English Walnuts, that is! Majestic to behold, Walnut trees, are among my favorite trees, and seeing them laden with nuts is a joy.

The ‘foreign tree’

Walnut trees (Juglans regia) are well integrated foreigners in our northern latitudes. Their home is in the warm, and fertile regions of south-east Europe, northern Greece, northern Italy, and France, where they are widely cultivated. Walnuts reached the ‘Low Countries’ north of the Alps in the pockets of Roman soldiers. But, it took several centuries before they really made themselves at home. Teutonic tribes, who gave them their name, apparently regarded them as an oddity, which is expressed in the name they gave the tree: ‘Walnut’ is derived from the Germanic word ‘welsh’, meaning foreign.

They did not reach Britain until the 16th-century and are only found in the warmer, southern parts. The Roman nut became known as the ‘English Walnut’, perhaps to distinguish it from the American walnut (Juglans nigra), or the Pecan nut (Carya illinoinensis). So, it seems this ‘foreigner’ has not only well adapted to its new home but has also been adopted by the locals, who think of it as one of their own.

A southerner in northern climes

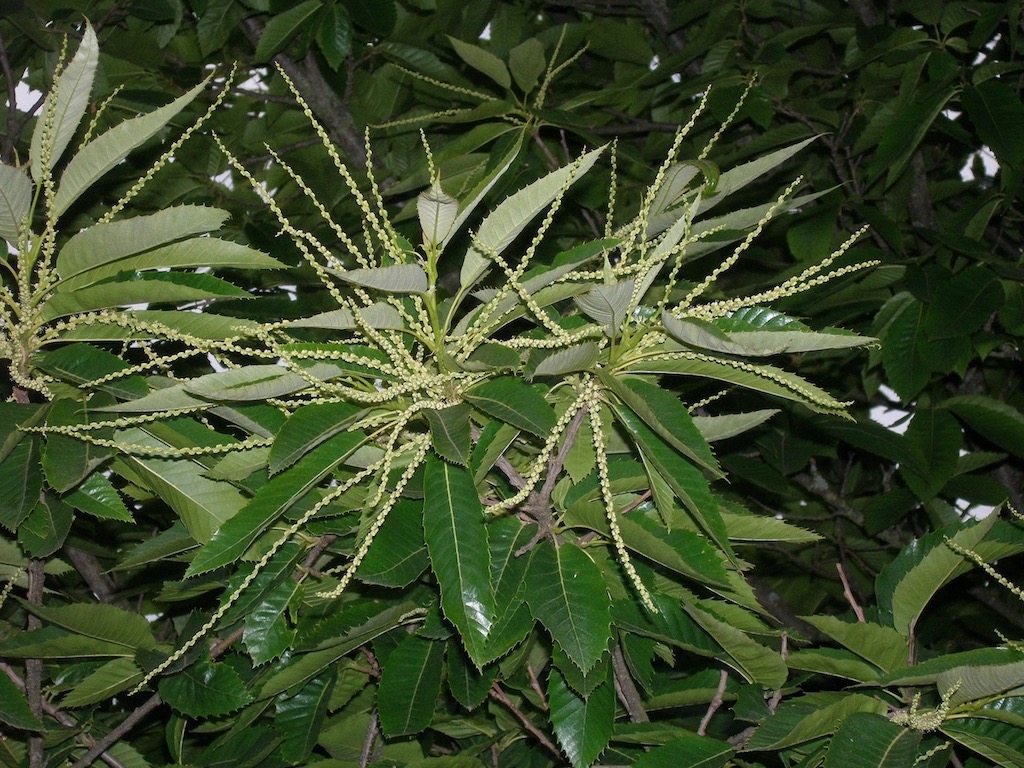

Although in time walnuts adapted quite well to the much harsher northern climate, their southern origin becomes evident in spring. Despite the fact that they come into flower quite late (April), they remain vulnerable to late frosts, which can quickly ruin the prospects of a good harvest.

A generational tree

In previous centuries, walnut trees were considered so valuable that they were specifically itemized in the will. A productive grove could cover a good part of a family’s livelihood. But that aside, planting a walnut orchard was an investment in the future: walnut trees are slow to mature. Although they start to produce nuts from the tender age of 15 years, they don’t become fully productive until they have reached the age of thirty. A mature tree produces about 50kg of nuts per year.

The American Cousin

The American (Black) Walnut is quite a different fellow. They are native to the US and occur wild throughout the eastern United States. However, they are not as well-loved as the ‘English’ variety, since they have the rather unsocial habit of emitting a chemical from their roots that inhibits, and eventually kills other plants in its vicinity. Besides, they are incredibly hard to shuck. People report placing them on their driveways and driving the truck over them in order to crack their shells. Crows & co have picked up on this trick. The birds strategically place nuts in the flow of traffic (e.g. at stoplights) in order to enlist our help in cracking the nuts.

Foraging

In a good year, a mature walnut tree is laden with nuts, which begin to fall in late September/early October, depending on your growing zone.

The nuts are covered by a hard, green hull that is exceedingly difficult to remove and besides, will stain your hands, clothes, and work surface. Wear gloves, if you don’t want your hands to look like you have been chain-smoking. It is best to harvest the nuts when they are fully ripe, at which point the green cortex will split open to reveal the nut inside, or sometimes it disintegrates into a black mush, leaving the nut behind.

Remove the black stuff as much as possible. It is very high in tannin and can affect the quality of the nut inside. Once you have removed the outer cortex wash the nuts. Put them into a bucket of water. This will naturally separate the good ones from the rotten ones. Bad walnuts tend to float, while the good ones will sink.

After washing the nuts, you can either shuck them or dry and store them for later use. If dried and stored properly, walnuts can keep for a year. Shucking exposes them to oxygen, which will cause them to turn rancid more quickly, due to their high levels of unsaturated (as well as saturated) fats. Keep the nuts in a cool and dark place where there is no danger of worms or vermin looking for a free lunch.

American Walnuts are much harder to crack than English walnuts. It is said that soaking them in water for 8 hours prior to cracking makes the job much easier. For English Walnuts, this is not necessary. They readily succumb to the persuasive powers of an ordinary nutcracker. Black Walnuts need a more forceful treatment.

Walnuts are very rich in oil – 2 kg of nuts will yield about one liter of oil. which is considered a delicacy. It is not so easy to obtain from your foraged nuts, though. Native Americans are said to have boiled the nuts to extract the oil. But this also destroys some of their nutrients.

Walnut oil has a delicious nutty flavor and is excellent in salad dressings or home backing to impart a delicate nutty flavor.

Most of all, forager appreciate walnuts for their delicious ‘meat’, which can be used in both sweet and savory dishes. (see recipes below)

Medicinal uses

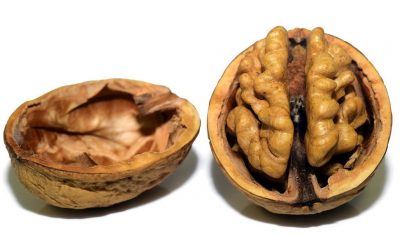

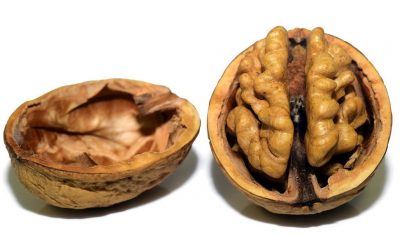

The soft kernel on the half-shell vaguely resembles a brain, surrounded by the protective cover of the cranium. The ancients took this likeness to mean that the nut must be good for the brain. (according to the doctrine of signatures). Scientists have confirmed that walnuts are indeed beneficial for the brain. This is due to their nutrient content, and especially the omega-3 fatty acids (of which walnuts are a rich source). Omega-3 fatty acids support the body when it comes to dealing with stress and is said to help alleviate depression. (see https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/omega-3-fatty-acids-for-mood-disorders-2018080314414)

Native Americans have used various parts of the tree, not just for food, but also as medicine. The leaves and root bark was used in anti-parasitic preparations and to treat skin diseases. The root bark is very astringent and makes a good anti-inflammatory wash that can be applied to herpes, eczema, and scrofula. Taken internally, it stops diarrhea, stays the flux, and dries up the flow of milk in nursing mothers.

Dyeing

The leaves repel insects and can be used as an ad hoc insecticide. The hulls, husks, leaves, and bark are all used as vegetable dyes to yield various colors ranging from yellow to dark brown or black.

Paints

The oil is drying and can be used in oil paints as an alternative to Linseed oil. Recently, powdered shells have been incorporated into new types of ‘designer paints’ to produce interesting textures or in-floor paints, to produce an anti-skidding effect.

Recipes

Pickled Walnuts

If you want to pickle walnuts, you have to pick them while they are still green and hanging in the tree. They have to be in an unripe state so that the inner shell is still soft and hasn’t turned woody yet. Typically, they should be picked in June.

Prepare a brine: 6oz salt to 1 quart of water.

With the help of a long needle poke the walnuts all over (don’t remove the green hulls) and cover with the brine. Steep for about 1 week.

Drain, and repeat: cover with fresh brine for another week.

Drain again. Spread the walnuts on a tray and let the sun dry them. Turn them from time to time.

When the walnuts are dry and have turned black, fill them into pickling jars. (Kilner jars, mason jars))

Prepare a spiced vinegar with:

- 1oz mixed peppercorns

- 1oz allspice

- ¾ inch ginger root (fresh)

Add some dried chilies or coriander seeds, if you like. Lightly crush the spices and place them into a muslin bag. Simmer the bag in the malt vinegar for 10 minutes. Then let the vinegar cool down before removing the spices. Pour the vinegar over the walnuts and make sure the liquid covers them. Close the jar tightly. Macerate for 6 – 8 weeks before tasting them.

Stuffing

Walnuts make an excellent stuffing for mushroom, marrows, or puff pastry parcels.

Ingredients:

- 12 medium-size mushrooms caps

- 1 tbs. olive oil

- 1 tbs. butter

- ½ cup finely chopped onion

- 2 tbs. coarsely chopped walnuts

- 1 garlic clove, peeled and minced

- 5 ounces frozen spinach, thoroughly defrosted and squeezed to remove most of the liquid

- 1 oz feta cheese, crumbled

- 1 oz Gruyere cheese, crumbled

- 2 tbs minced fresh dill

- salt and freshly ground black pepper and nutmeg to taste

Method:

Preheat oven to 400° F. Clean the mushrooms and remove the stems. In a small skillet, heat the olive oil and butter. Add the onion and cook over medium heat, cover and sauté until soft.

Add walnuts and cook for another minute. Add the spinach and stir continuously for about 5 minutes. Take off the heat and cool slightly. Stir in cheeses, dill, nutmeg, and salt and pepper, to taste.

In an oven-proof pan arrange the mushrooms, cavity side up. Plop a wallop of the spinach/walnut mixture into each mushroom cap and bake for 8 to 10 minutes or until the filling turns brown and the mushrooms are thoroughly heated.

Walnut Liqueur

In Italy and France, walnut liqueur is considered a regional specialty. ‘Nocino’ in Italian – although there are many versions of the ‘original’ recipe. The idea is simple: macerate green, unripe walnuts in a blend of clear alcohol, (e.g. grain alcohol), and syrup.

Method

In June, when the Walnuts are still green and soft inside (traditionally on St. John’s Day=Midsummer), pick your nuts straight from the tree. Wash and quarter the nuts.

Remember to wear gloves!

Fill a large jar with the nuts and add some spices, such as a couple of cinnamon sticks and a few cloves and perhaps a vanilla bean. Chop up an organic, untreated lemon (or orange, if you prefer) and add to the mixture. Pour in about 1 ½ pound of sugar and cover with 3 liters of grain alcohol. Close the lid tightly and steep for about 6 weeks. Keep in a warm dark place.

Test the liquid and adjust to suit your taste. Strain through filter paper and bottle. Store in a cool place.

Green Walnuts preserved in Syrup – from Mrs. Grieves – A Modern Herbal

‘Take as many green Walnuts as you please, about the middle of July, try them all with a pin, if it goes easily through them they are fit for your purpose;

lay them in Water for nine days, washing and shifting them Morning and Night;

then boil them in water until they be a little Soft, lay them to drain;

then pierce them through with a Wooden Sciver, and in the hole put a Clove, and in some a bit of Cinnamon, and in some the rind of a Citron Candi’d:

then take the weight of your Nuts in Sugar, or a little more; make it into a syrup, in which boil your Nuts (skimming them) till they be tender;

then put them up in Gally potts, and cover them close.

When you lay them to drain, wipe them with a Course cloth to take off a thin green Skin. They are Cordial and Stomachal.’

– (From The Family Physician, ‘by Geo. Hartman, Phylo Chymist, who liv’d and Travell’d with the Honourable Sir Kenelm Digby, in several parts of Europe the space of Seven Years till he died.’)

Walnuts are incredibly versatile – even if they are not the star ingredient, they never fail to give a dish a refining note. I sprinkle them on salads or use them instead of pine nuts in a pesto blend. They are also fabulous in desserts and cakes.

Caution:

People who are allergic to nuts should stay away from walnuts and all products derived from them or containing them. Likewise, people who are scared of calories should treat this nut with respect. However, replacing some of your normal dietary fat with walnut oil can be a very wise choice as walnut oil has an excellent nutritional profile and can help to fight free radicals while lowering cholesterol levels. Walnuts are a good source of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.

Always wear gloves when handling walnuts – especially as long as they are still green. And leave some for the wildlife – it is an important source of food to carry them through the winter.

Image by Yaayaa Diallo from Pixabay

Image by Yaayaa Diallo from Pixabay

Native Americans set up semi-permanent sugar camps in the forests to which they traveled for the annual ‘sugaring season’ (from about mid-February to early April). The camps usually consisted of two structures: a small birch-bark-covered lodge where the utensils were stored and the sugaring lodge, which also served as a temporary living space.

Native Americans set up semi-permanent sugar camps in the forests to which they traveled for the annual ‘sugaring season’ (from about mid-February to early April). The camps usually consisted of two structures: a small birch-bark-covered lodge where the utensils were stored and the sugaring lodge, which also served as a temporary living space. Before there were kettles, pots, and pans made of metal, the Native Americans used birch bark containers and vats made from moose skins. To heat the syrup, they would place red hot stones into these containers filled with the syrup. These were then cooled in the snow. Once the water had frozen into a sheet of ice, it was simply discarded.

Before there were kettles, pots, and pans made of metal, the Native Americans used birch bark containers and vats made from moose skins. To heat the syrup, they would place red hot stones into these containers filled with the syrup. These were then cooled in the snow. Once the water had frozen into a sheet of ice, it was simply discarded.

Composition of Pure Maple Syrup:

Composition of Pure Maple Syrup: