Ethnobotany is defined as the study of the relationship between people and plants, although the term is most commonly used to refer to the study of indigenous uses of plants. It is, so to speak, the marriage between cultural anthropology and botany, a study that sets out to investigate the roles of plants as medicine, food, natural resources, or as gateways to the gods. It is considered a relatively young field of study; officially it has only been recognised as an academic discipline for about one-hundred years.

However, to investigate the uses of plants is among the most primary of human concerns, and all cultures around the globe have pursued this knowledge for tens, if not hundreds of thousands of years – it’s just that it wasn’t called ‘Ethnobotany’ then.

For any field of study to morph into a scientific discipline necessitates a certain distance has to open up between the observer and the observed. For it is in this ‘gap’ that an objectifying science can emerge. In other words, people who are deeply immersed in the world of plants simply ‘study by doing’. They don’t interpret the meaning or function of their activities, they simply explore and do what is useful, or necessary in a given situation. But scientific study requires that the student takes a step back and views the object of investigation from a certain distance so as to be able to recognise patterns and laws, which can serve as models that can be abstracted in order to facilitate understanding. Direct emotional involvement and the social context of meaningful relationships is usually stripped from the description in order to represent an ‘accurate’ view of the observed.

An empirical investigation, on the other hand, represents the exact opposite approach. The investigator must be involved with the object of study, and fine-tune their perceptions so as to notice subtle, subjective impressions and effects, (which scientists consider ‘not credible’).

Traditional healers of all cultures follow the empirical approach to learning about plants. They are less interested in the ‘constituents’ than in the impressions the whole plant, embedded in their environment, makes upon their psyche.

Scientists find it baffling to understand how these traditional healers, without the use of elaborate equipment or any formal schooling, can be so adept at identifying plants, discerning their uses and finding effective remedies among the thousands of species that surround them. Or how they manage to discern combinations of plant species that work together synergistically, but are completely inert when used by individually. And they assume a long and painful road of trial and error experiments to learn how to render poisonous plants harmless by a series of complicated processes.

In traditional societies, people’s relationships with the natural world are complex and imbued with meaning. This layer of significance is completely lost on the researcher who only attempts to source some bioactive compounds to develop novel drugs. But an ethnobotanist, who is trained in cultural anthropology as well as in botany and sometimes in phytochemistry as well, understands that although each of these layers offers clues, we will never be able to fully ‘get’ the meaning of a particular plant/human relationship without understanding its whole cultural context.

Ethnobotany is a vast field that encompasses myriad different uses of plants, ranging from their most mundane purposes to their spiritual significance. However, we must be careful not to confuse Ethnobotany with Economic Botany – the study of the uses of plants.

While many articles will also touch on the economic or utilitarian uses of plants, the real purpose of this project is to try open a window to another way of being in and understanding the world, which is currently in danger of being lost.

The dominant mindset only understands economic terminology and tries to place a monetary value on everything in our living world. I offer these pages as a voice in the wilderness in an attempt to rescue the more fragile threads that are the repositories and transmitters of cultural knowledge. It is, after all our way of seeing that shapes the world we live in. In that spirit, I am attempting to go beyond the bare bones of biomarkers and molecules, to search for traces of meaning, the anima that ensouls the natural world.

It is my firm belief that Ethnobotany can serve as a window that can open our eyes to another way of seeing, a world in which we are not the masters of the universe, raping and pillaging the earth’s natural resources, but in which we are the caretakers and co-creators of this Garden of Eden that is our heritage.

12 amazing superfood properties of Cacao

This article is about the amazing nutritional superfood benefits of Cacao and high Cacao content chocolate.

History of the Cocoa Tree- Theobroma cacao

This article is a short introduction to one of my favourite plants: Cocoa – Theobroma cacao, the food of the gods.

Ever heard of Lion’s Mane Mushrooms?

I never heard of Lion’s Mane mushroom until I found one in the woods. I am so glad it came into my life – and changed it for good!

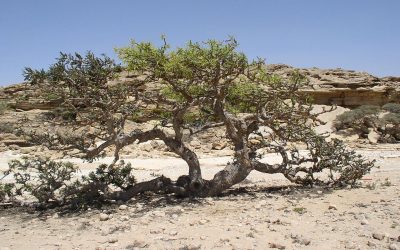

Frankincense (Boswellia sp.)

Frankincense is well-known as that stuff that is burnt in church. But what exactly is it, and where does it come from?

Tree Profile: Yew (taxus baccata)

Few western European trees are as enigmatic as the Yew. Dark, brooding and sometimes eery, each Yew tree very much has its own personality.

How to Make Natural Body-Care Products?

A short introduction to how to make natural homemade cosmetics. Find out how easy it is to make body butters and bath salts at home.