Why Hawthorn is your heart’s best friend

Plant Profile: Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna)

When the Hawthorn dapples the hedgerows with its pinkish-white blossom, we know that spring is here to stay. Typically, Hawthorn starts to flower at the end of April or the beginning of May, which is why it is also sometimes known as ‘Mayblossom’ or simply as ‘May’. Linnaeus originally named the species Crateagus oxyacantha, a combination of kratos, meaning ‘hardness’ (of wood), ‘oxus’ which means ‘sharp’ and ‘akantha’ for ‘thorn’. But there is ambiguity over which precise species Linnaeus meant and thus this old name has been rejected. The new name is Crataegus monogyna, which refers to the fact that this particular species only has one seed.

Description

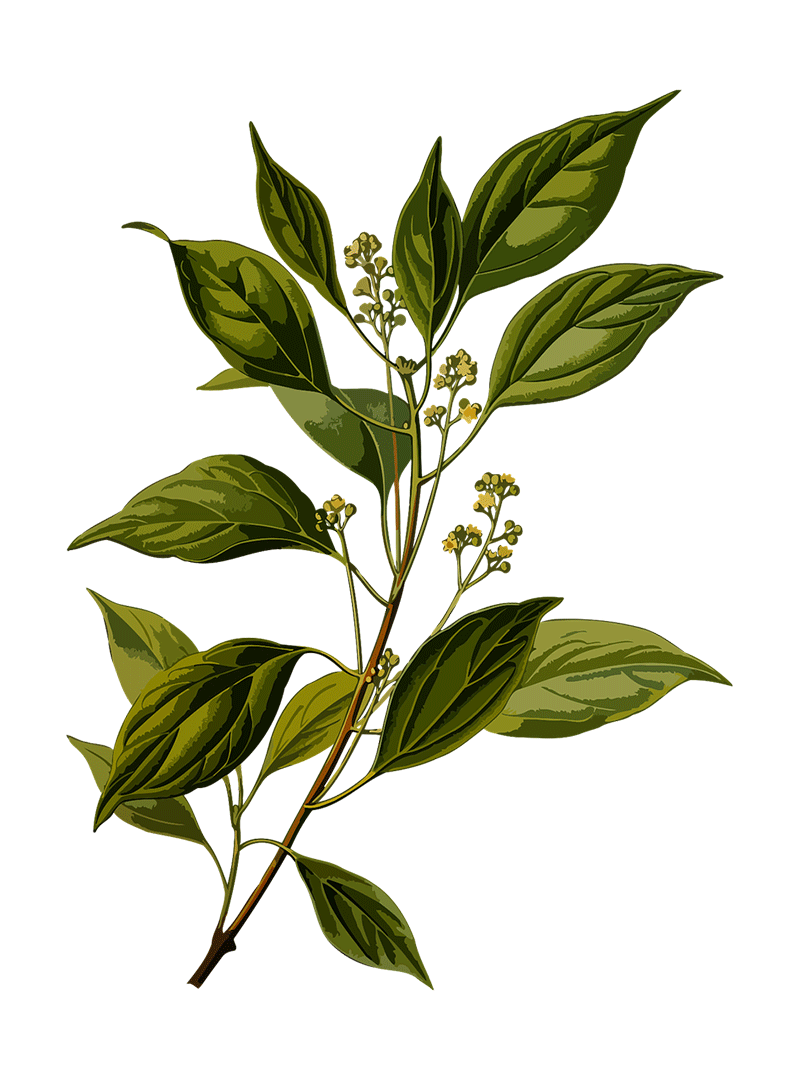

Hawthorn grows as a small, hardy tree that rarely grows to more than 30 ft. It is a member of the rose family, in the extensive genus of Crataegus. Taxonomists still argue over the actual number of species that belong to this genus, but conservative estimates range from about 200 to 300 species. Hawthorns are quite ‘promiscuous’ which results in many cross forms that some botanists consider mere variations, while others deem them separate species.

During the flowering season in late April or early May the small, white five-petaled flowers grow in showy clusters that cover up almost every inch of the tree. The deeply cut, 3-lobed leaves are about 3″ long and appear before the flowers. They are dark green on top and paler bluish-green underneath. In September, an abundance of bright red ‘haws’ glow in the hedges, looking very much like ‘mini rose hips’. Although edible and attracting much wildlife they are not especially palatable to humans.

Habitat and Ecology

The genus is most diverse and widespread throughout North America. But it is well represented in the entire Northern Hemisphere, including all parts of Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and even China. Crataegus monogyna is not native to North America.

Hawthorns are most familiar as hedgerow trees. They are undemanding as far as soil conditions are concerned, but prefer full sun. They may be found in open woodlands, along their edges or, most distinctively, as lone trees on open hillsides.

For wildlife, a hawthorn hedgerow is an ideal habitat: the thick, dense and impenetrable tangle of thorns provides a safe habitat for many small animals and birds.

Crataegus monogyna is not native to North America, but it was introduced there as a hedge plant, in the 1800s. Birds have been instrumental in distributing their seeds far and wide. They seem to prefer these berries to those of the native varieties. The advance of industrial farming in North America has pushed Crataegus into decline. No longer valued as a hedgerow plant bordering fields to protect against soil erosion it is now viewed as problematic and invasive.

History

Hawthorn is so common throughout the country that it hardly needs a description. Unassuming and inconspicuous, its petite and straggly appearance does not really inspire awe. Like an old familiar friend it waves its windswept branches from the top of a hillside or greets us as we pass it on the old familiar track. Yet, there is something quintessentially British about this tree. It is hardly surprising that its ancient roots are deeply entwined with the myths and folklore of our ‘Dreamtime’.

Etymologically, the name at first seems to indicate nothing more than a utilitarian function for which indeed it is still very commonly employed: Hawthorn makes a superb and quickly setting natural defense. A dense thorny Hawthorn thicket is quite impenetrable. Its fast development (appropriately it is also known as Quickset or Quickbeam) aids this purpose, as does the fact that its branches become increasingly dense the more they are cut or eaten.

But in the mindset of the ancients, a hedge was more than just a living fence. A hedge signified the boundary between the known, safe, and civilized world and the wild, mysterious wild yonder. The word ‘hedge’ derives from the old English ‘Haga’ also found in Hagathorn’, which is another name for Hawthorn. Both share the same Germanic root ‘hag’.

Etymology

In old English, a ‘hag’ was not just an old, ugly woman, but is cognate with ‘haegtesse’ – a woman of prophetic powers, and ‘hagzusa’ – spirit beings and ‘hedge riders’. These wood sprites were thought to reside in the ‘between worlds’, ie, between the worlds of everyday reality and ‘the otherworld’. As spirit beings, these sprites could easily traverse the boundaries between the worlds. Likewise, their human counterparts were the healers, seers, and soothsayers who were also thought to be able to travel between these worlds. Thus, Hawthorn signifies protection, yet it is also seen as a gateway to the spirit world.

In folk medicine, its primary use is for protection against all manner of evil spirits, and demons who were apt frighten hapless passers-by. Carved hawthorn amulets were worn for protection or hung above doors to keep bad spirits at bay.

Mythology

Hawthorn features in both pre-Christian and Christian symbolism. In Christian mythology, it is said that the crown of Christ was made of Hawthorn. Some authorities have claimed that the Holy Spirit has a certain peculiar affinity with thorn trees. The burning bush apparition mentioned in the Bible is thought to have been a thorn tree.

In British Christian mythology, the most famous Hawthorn is the Glastonbury Thorn, which could long be seen as a lone figure on the slope of Wearyall Hill. (Sadly, vandals have destroyed this tree.) According to legend, Joseph of Arimathea, an uncle of Jesus, had traveled to Britain with the intention of finding a place to bury the holy cup (grail) that had held the blood of Christ at the crucifixion. When he first set eyes on the Holy Isle of Avalon, he struck his staff into the ground on Wearyall Hill. At once it burst into flower. Joseph of Arimathea took this as a sign to establish the first Christian Church of England right there, where today lies the little market town of Glastonbury.

Descendants of that original miraculous walking stick have been transplanted as cuttings and now decorate various Christian sites around the town. To this day, these special trees burst into flower not once, but twice a year: first in May, when it is right and proper for all Hawthorn trees to flower, and then again at Christmas, to mark the birthday of Christ.

Folk Traditions

Hawthorn is also associated with the old Beltain custom of ‘fetching the May’. Beltain, which takes place on May 1, is a celebration of spring and the return of the life-force that rejuvenates the land. Hawthorn’s abundance of flowers that burst into blossom just at the right time seems eminently suitable to mark this glorious time of the year. People would tie colorful ribbons into the branches of the tree to symbolize their prayers and wishes.

The flowers exude a peculiar smell that is often likened to the odor of rotting meat. Hawthorn is fertilized by insects that are attracted by the smell of carrion, a smell that has also been associated with the plague. This is why, despite the fact that Hawthorn is very much loved, it is never brought inside the house.

The scent has also been associated with the perfume of sexuality, which better fits its fertility connotations in association with the Beltain celebrations. Whatever one might associate with the scent, it is unlikely it will go unnoticed as the flowers announce their presence from afar.

Food uses

The flowering tops can be used for making a heart-friendly breakfast tea (see below).

In the autumn, the tree is laden with hard, red berries that look like miniature rose hips. Unfortunately, Crataegus mongyna is rather mealy and not very tasty. The meager pericarp layer is extremely dry and almost devoid of flavor. There are, however, related species with much better-tasting fruits. Some are even juicy enough to process into a jelly. If need be Hawthorn berries can be dried and ground into a kind of flour substitute. However, as they contain no gluten this is not a flour to make bread with.

Medicinal Uses:

From an ethnobotanical perspective, Hawthorn is a very interesting plant. Since it is a very large and widely distributed genus people from China to Europe to North America have used their specific native species in similar ways.

Parts used:

Flowering tops, ripe fruits, leaves

Collection:

The flowering tops are harvested in May. Dry quickly in the shade to avoid discoloration. The berries are collected in the autumn. Dry quickly and thoroughly to prevent mold.

Constituents:

Fruit: saponins, glycosides, flavonoids, cardioactive glycosides, ascorbic acid, condensed tannins.

Flowers: cardiotonic amines

Crataegus does not contain any single active constituent that phyto-pharmacologists will get excited about – it sports no ‘super compounds’ that can be developed into new drugs. Instead, it is the unique synergy of its composition that creates its marvelous effects – and which so far has defied replication in the laboratory.

Hawthorn is most valued for its tonic action on the heart. It has an undisputed regulatory, or tonic effect that provides an immensely useful and safe remedy for beginning cardio-vascular disease. Heart disease is the leading cause of death, particularly in developed countries.

The flowering tops as well as the berries are medicinally active. They regulate the blood-pressure via a dual action: they stimulate both the coronary arteries and the heart muscle itself. They dilate and relax the blood vessels, thus lowering blood pressure, while gently stimulating the heart muscle, increasing the pulse rate. This takes the pressure off the heart muscle and thus improves its overall efficiency.

Hawthorn relaxes the nerves that supply the heart, which helps to relieve the symptoms of stress, tightness in the chest and angina. It also regulates an irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) and palpitations. Hawthorn is a valuable supportive long-term remedy for the general weakness of the heart caused by infectious diseases such as diphtheria or scarlet fever. It improves the overall function of an aged and tired heart muscle. It may be used preventatively and is especially recommended for people who are under constant pressure and stress, or remedially, for those recovering from a heart attack.

According to Chinese and Japanese studies, Hawthorn clearly shows a positive effect on the whole coronary system and can reduce ‘bad’ cholesterol, one of the most significant contributing factors of heart disease.

Hawthorn improves the peripheral blood flow, thus improving oxygen supply to the limbs and to the head. In combination with Gingko it has a beneficial effect on memory.

Hawthorn has also been used for nervousness and as a digestive tonic to help ‘move’ stagnant food (Chinese medicine) and to aid the digestion of fatty foods. It is also considered useful as a diuretic and a urinary tonic. The old herbalists seemed to value this aspect of Hawthorn’s healing virtues especially highly.

Hawthorn is the best overall heart tonic available in the herbal pharmacopeia. It is even recognized in allopathic medicine and is included in the ‘Commission E’ list of medicinally useful plants. Its gentle, tonic action and safety record make it an ideal and safe herb for conditions afflicting an aging coronary system and heart. But it is an alterative and tonic remedy, which means best results are achieved when it is taken over long periods of time. Instant results should not be expected. It contains no digitalis-like compounds or other cardio-active constituents that build up in the body over time. There is also no record of drug interference, even with other cardio medicines. Thus, Hawthorn tops or berries taken as a tea or tincture can be taken over long periods of time without ill-effects. (Of course, allergies are always possible, but with this herb, they form a very small exception to the rule.)

Ref: Hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) in the treatment of cardiovascular disease

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3249900/

UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS Characterization of Phenolics from Crataegus monogyna and Crataegus laevigata (Hawthorn) Leaves, Fruits and their Herbal Derived Drops (Crataegutt Tropfen)

PHENOLIC CONTENT AND ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY OF CRATAEGUS MONOGYNA L. FRUIT EXTRACTS

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8193/140b3f344ce5633451fe0e5d63499cd1a40f.pdf

Heilpflanzenpraxis Heute, Siegfried Bäumler, Elsevier 2007