Gums, Resins, Latex

Gums, resins and latex do not generally come to mind when we consider the importance of plant products. Vegetables, fruit, wood, maybe medicinal herbs, essential oils, fibres and dyes are far more present.

What are gums and resins?

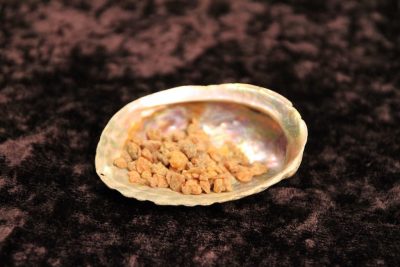

Simply put, gums and resins are the sticky stuff that some plants excrete when the outer ‘skin’ or bark has been injured.

Most familiar to us are Frankincense and Myrrh, the precious gifts of the three wise men brought to honour the birth of the baby Jesus. These two oleoresins come from oriental two different species of the Burseraceae family, also known as the ‘balsam tree’ family.

While Frankincense and Myrrh are arguably the most famous resins, they are by no means the only ones. Resins, gums and latex are widespread in the plant kingdom, and many play an important role in our everyday lives.

What are gums and resins used for?

Gums and resins are used as adhesives, emulsifiers, and thickening agents. They are added to varnishes, paints and ink, lend their aromas to perfumes and cosmetics, and even play a role in the pharmaceutical industry.

The ancients burnt them as offerings to the Gods. They believed that scents are the nourishment of the gods since they can’t partake of solid food. In Ancient Egypt, gums and resins played a notable role, not just as incense, perfume and medicine, but most importantly, in mummification practices.

Aroma is the subtle (or not so subtle) medium that transmits messages below the threshold of conscious awareness. This type of communication is ubiquitous in the natural world – an invisible signal to potential partners or foes.

Let’s examine the different chemotypes of gums, resins and latexes.

Balsam

This generic term describes all kinds of fragrant, soothing, resinous substances of plant origin. But in chemistry, the term refers to a specific class of resinous substances that contain large amounts of cinnamic- and benzoic acids, and essential oils. Balsam of Peru, Tolu Balsam, Balm of Gilead, and Copaiba balsam are common examples. Their physical properties vary greatly – they may be clear and viscous or dark and sticky, but all coagulate when boiled and solidify when exposed to air.

Medicinally, balsams are used to treat skin problems and respiratory diseases. They are a common ingredient of cosmetics, skincare products and perfumes. However, benzoic acid is a known allergen that can trigger severe reactions. Caution is advised.

Gums

Chemically speaking, gums are complex polysaccharides (Carbohydrates) that are either water-soluble or water absorbent. But, they are not soluble in oil.

Gums are extracted from the resinous sap or the endosperm of certain seeds. Guar Gum, for example, comes from the seeds of a herbaceous plant, Cyamopsis tetragonolubus, an African member of the pea family.

Gums are widely used in the food industry as emulsifying and thickening agents. The pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries also utilize them, especially in skincare products. And they are even used to manufacture inks, paper, watercolours and adhesive, like the gum on the back of stamps. Water-soluble gums are found in dietary supplements to bind endotoxins and promote excretion by adding bulk to the stool. A prime example, Psyllium seed, used to treat mild cases of constipation. Even seaweeds can yield gums, like Agar-Agar, used as a thickener instead of gelatine.

Resins

Resins are terpene-based compounds that are chemically completely different from gums. Terpenes constitute one of the largest groups of plant chemicals, and they can be very complex. Unlike gums, resins are not water-soluble but may be either oil- or alcohol soluble, depending on the specific chemical composition. Resins are far more common than gums.

Most resins are obtained by a process known as ‘tapping’ or ‘bleeding’, whereby incisions are cut into the bark. The resin exudes through the incision and is collected in buckets attached underneath. Trees can be bled several times, and it is possible to harvest resins sustainably. But the deliberate injury does put a considerable strain on any tree, and strict limits to the number of incisions and period of productivity must be applied.

Recent research shows that the carbohydrates of these exudates are important energy reservoirs for the trees, and that excessive tapping reduces the numbers of flowers and the size and viability of their seeds. Guidelines are especially needed when the resin is collected from wild populations, where regeneration is left to nature.

In the past, resins were far more commonly used in industrial processes. Today, many have been replaced by synthetic alternatives. But their medicinal properties are still used in natural medicine.

Oleoresins

Oleoresins are classified as terpene compounds that are rich in volatile oils. They are softer and more pliable than other resins and provide a valuable source of essential oils used in perfumery or as aromatic fragrances for household products. Occasionally, the term ‘Gum-Resin’ can be found in the literature, but this is a confusing oxymoron and should not be used.

Latex

Latex is a thin, slightly sticky sap, usually white or colourless, that coagulates when exposed to air or boiled. Just how elastic the resulting latex will be, depends on its specific chemical composition. The greater the content of Cis-polyisoprenes, the greater the degree of elasticity.

The best known and economically most significant plant-based latex is rubber, which comes from the South American Rubber tree. When first discovered, it triggered a whole ‘boom and bust economy in the Amazon. But the glamorous mirage quickly vanished when, in an act of biopiracy, the seeds of the precious tree were stolen. The seeds were taken to India, where they gave rise to the first rubber plantation, thus breaking the monopoly and dependence on the South-American supplies.

However, it wasn’t long before natural rubber was replaced by synthetic alternatives and plastics, and the whole industry diminished in importance.

Latex has many uses: as sealant paints, rubber tires, insulating sheathing for electrical wires or rubber gloves, boots and other kinds of eclectic apparel.

We often forget the role that plants have played as sources of materials for our every need. Even modern industry can’t do without them.

Image by

Image by