Foraging: Sweet Chestnuts (Castanea sativa)

Nothing quite conjures up the magical atmosphere of autumn as the warm, sweet scent of roasted chestnuts. It immediately invokes images of bonfires and harvest feasts. When the days are getting shorter and there is that crisp little nip in the air, when the leaves turn bright in color and spread a thick carpet on the ground, when the earth smells musky and moist from the rain, the chestnut season is upon us.

Description

Sweet Chestnuts, which must not be confused with Horse Chestnuts, belong to the family of the Fagaceae, the Beech-Family, which comprises several genera and numerous species of trees with edible nuts, such as acorns and beechnuts.

They are at home in the temperate zone and shun excessively cold and wet regions. In Europe, their range extends as far north as southern England, but they are most comfortable in a Mediterranean climate, where they form quite extensive natural stands.

The North American native species (Castanea dentata) has largely been replaced by the Chinese species, which was imported in the early 1900s. Unfortunately, the imported trees were infected with a virulent blight that spread rampantly and wiped out almost the entire population of native Chestnut trees.

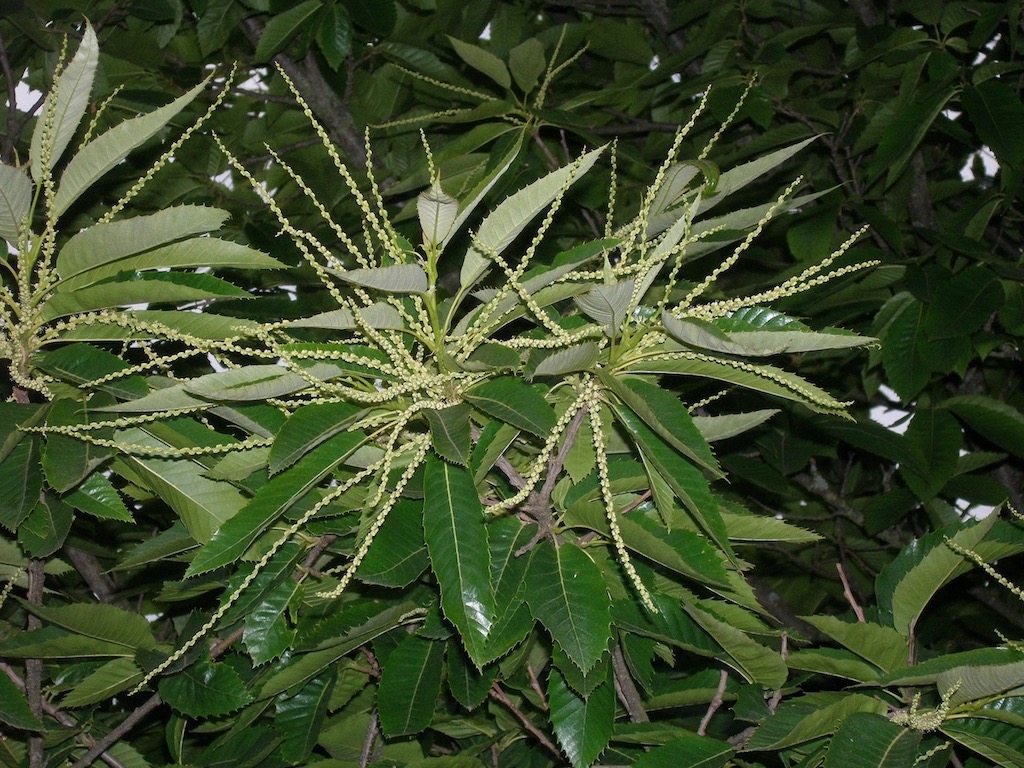

Sweet Chestnuts grow into beautiful tall trees, with elegant large, but slender leaves, with serrated margins. The leaves develop before the flowers appear in June. They form long golden-yellow catkins reminiscent of arboreal fireworks. The nuts develop in early autumn. They are protected by a very prickly outer shell (cortex). When the cortex splits it reveals two or three nutlets that are shaped like pixie-hats, with a pointed tip and tiny tuft of white hair. In natural stands, only one of the nuts develops fully.

Commercial Chestnuts are derived from a cultivated variety, in which the underdeveloped nutlets are missing altogether. The bulk of the commercial crop is grown in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France, where chestnuts still play an important part in the traditional cuisine.

Foraging

If you are lucky enough to have a Chestnut tree in your neighborhood, the temptation to collect the very first nuts that fall to the ground in September is almost irresistible. But the early nuts are not yet fully ripe and are usually not worth the bother. It is better to wait for another couple of weeks. By October, the nuts are plump. The outer, bristly coats should be cracked open. Now it’s time to get busy, otherwise, the forest folk, the squirrels, and wild boar will beat you to it. The shells are really prickly, so thick rubber gloves come in handy. The easiest way to remove the cortex is by gently stepping on the nuts and rolling them around on the ground underfoot until the outer shell comes off by itself. Check the nuts for little holes. That would indicate that the worms are already feasting. Worms tend to be more of a problem after heavy rains or when the nuts have been lying on the ground for too long.

The most tedious part of the Chestnut harvest is not the collection, but the shelling. A fibrous membrane adheres to each nutlet beneath the shell. It clings to every crevice and cleft.

There are several methods to remove this membrane, and the method of choice depends on how you intend to use the nuts.

But, regardless, the first step is to remove the outer husk. Cut a little cross on the bottom surface (of each nut. Without this precaution, they explode violently when being roasted. But even if you boil them, cutting the outer shell makes the process of shelling them and removing the membrane much easier.

To preserve Chestnuts for long-term storage you still need to shell them and to remove the inner membrane. Afterward, you can dry them quickly in the oven or dehydrator, to avoid mold. Once dehydrated, they need to be soaked in water prior to use. In France, a traditional method of curing the nuts was to spread them on the floor of a harvest hut and to smoke them for a period of time. Smoked nuts could be stored for up to a year.

Pan/Oven Method

Cut a cross on the flat side of each nut and place them in a heavy skillet. Add about half a teaspoon of butter per cup of chestnuts and roast at medium heat until the butter is melted. Put the pan in the oven at 475°F. After 10 – 15 minutes, remove the pan from the oven and take off the shells with a small sharp paring knife. It is a tedious process, but if done correctly, the inner skins will adhere to the outer shells, thus making the shelling process much easier.

Chestnuts are a wonderful, very nutritious wild food. Unlike most nuts, they are rich in both carbohydrates and proteins but contain very little fat and no cholesterol. This distinct composition has earned them their nicknames ‘l’arbre a pain’ in French, meaning ‘bread tree’ or the English equivalent, ‘the grain that grows on trees’. Their flavor and consistency are unique in that it lends itself very well to both sweet and savory dishes. A favorite is chestnut stuffing, but they can also be used in soups, nut loaves, cookies or desserts, or they can be ground into nut flour.

Recipes

Roasted Chestnuts

A simple and delicious way to enjoy Chestnuts is to simply roast them, either in the oven or on an open fire. In southern Europe, special chestnut roasting pans are used for this purpose, though they are not strictly necessary. They are basically frying pans that have holes on the bottom. But it is just as simple to roast the chestnuts in a regular pan. The important thing to remember is to make an incision on the bottom of each nut so that they don’t explode. Place in a pan and roast over a medium flame for about 15 min. The flavor is completely transformed by the process. Even if you intend to use them for other dishes, such as soups or stuffing, roasting them prior to any further processing is highly recommended. They also taste great straight from the pan or can be served with blue cheese and wine.

Stuffing

Minced chestnuts are excellent as stuffing for birds, such as pheasants or goose. Roast onions and garlic, add boiled and minced chestnuts and rice along with chopped celery sticks and apples. Stir an egg into the mixture and season to taste, e.g. salt, thyme, sage, rosemary, mugwort. Add wholemeal flour, oats or wholemeal breadcrumbs until the mixture has the right consistency, neither too dry, nor too wet. Judge the amounts by the size of the bird.

Chestnut Loaf

The above-described stuffing can also be adjusted to make a nice chestnut loaf. The chestnuts can be mixed with other nuts, e.g. peanuts or walnuts. Mix roughly half and half nuts and rice, add grated or finely chopped vegetables, e.g. zucchinis, mushrooms, onions, and garlic either sautéed or raw, add an egg and flour until everything sticks together nicely. Season to taste. Fresh herbs such as thyme, rosemary, and a touch of sage are nice. Grease a bread pan and fill with the mixtures. Bake in the oven at about 375 degrees until a crust forms on the top and the dough no longer sticks when pricked with a wooden stick. Serve with steamed vegetables and mushroom sauce.

Glazed Chestnuts And Winter Vegetables

- 2 large kumera (sweet potato)

- 4 large parsnips

- 4 small red onions, quartered

- 12 whole garlic cloves, skin on

- 1 tablespoon fresh rosemary leaves

- 1 ½ cups peeled/blanched chestnuts

- ½ cup maple syrup

- ½ cup olive oil

- salt, freshly ground black pepper

Cut kumara into large chunks. Cut parsnip in half lengthwise. Combine all ingredients in a baking dish; bake, uncovered in a hot oven (220°C) about 45 minutes or until the vegetables are tender and browned lightly. Turn gently halfway through cooking. Serves 6 to 8.

Curried Chestnut Soup

- 1 large onion, finely chopped

- 2 carrots, thinly sliced

- 1 zucchini, chopped

- 1 apple, grated

- 1 cup mushrooms, sliced

- 1 cup roasted chestnuts, minced

- vegetable seasoning

- ½ pint milk

- ½ vegetable stock

- 2 cloves garlic

- Curry powder

- Pinch cinnamon

- Chilies to taste

Sauté the onions and carrots until the onions are soft. Add zucchini and apple. Continue to sauté and stir. Add mushrooms. Sprinkle 1 tablespoon of vegetable seasoning and a teaspoon of curry powder and a pinch of cinnamon into the vegetables and continue to stir. Add one pint of water. Bring to the boil and add the roasted and minced chestnuts. Stir continuously so as to avoid any of the ingredients sticking to the bottom. Press the garlic into the soup. Add 1/2 pint of vegetable stock and 1/2 pint of milk and simmer until all the vegetables are cooked. Season to taste with extra salt, coriander, cumin, and chilies. Adjust liquid level so the soup is creamy but not too thick. A tiny touch of honey can blend the flavors perfectly.

Baked Apples With Chestnut Stuffing

Roast the chestnuts as described above, shell and mince. Mix with raisins, sultanas, oats, and honey. Core the apples and fill the hole with the stuffing. Place on a cookie sheet and bake in the oven until the apples are soft. Serve with vanilla ice cream.

Chocolate Chestnut Mousse

Chestnuts combined with cocoa and amaretto make a perfect ending for a festive dinner.

- 2 pounds of Chestnuts, peeled and cooked

- 12 Tbs. of sugar or honey or to taste

- 4 Tbs. of cocoa

- 4 Tbs. of amaretto

- 16 ounces whipping cream

Shell and peel chestnuts as described above. Boil until tender. Drain and add sugar or honey, cocoa, and Amaretto. Blend in a food processor until smooth. Beat whipping cream until stiff. Fold into the chestnut puree. Divide among dessert glasses. Chill. Decorate with whipped cream and chocolate shavings. Serves 10.

The mousse can also be used as a cake filling. Beware: it is very rich!