12 amazing superfood properties of Cacao

Medicinal and Therapeutic Properties of Cacao

This article is about some surprising medicinal benefits of real Cacao – the stuff that chocolate is made of.

It may come as a surprise, but Cacao is actually pretty healthy. (It’s my favourite ‘superfood’. 🙂

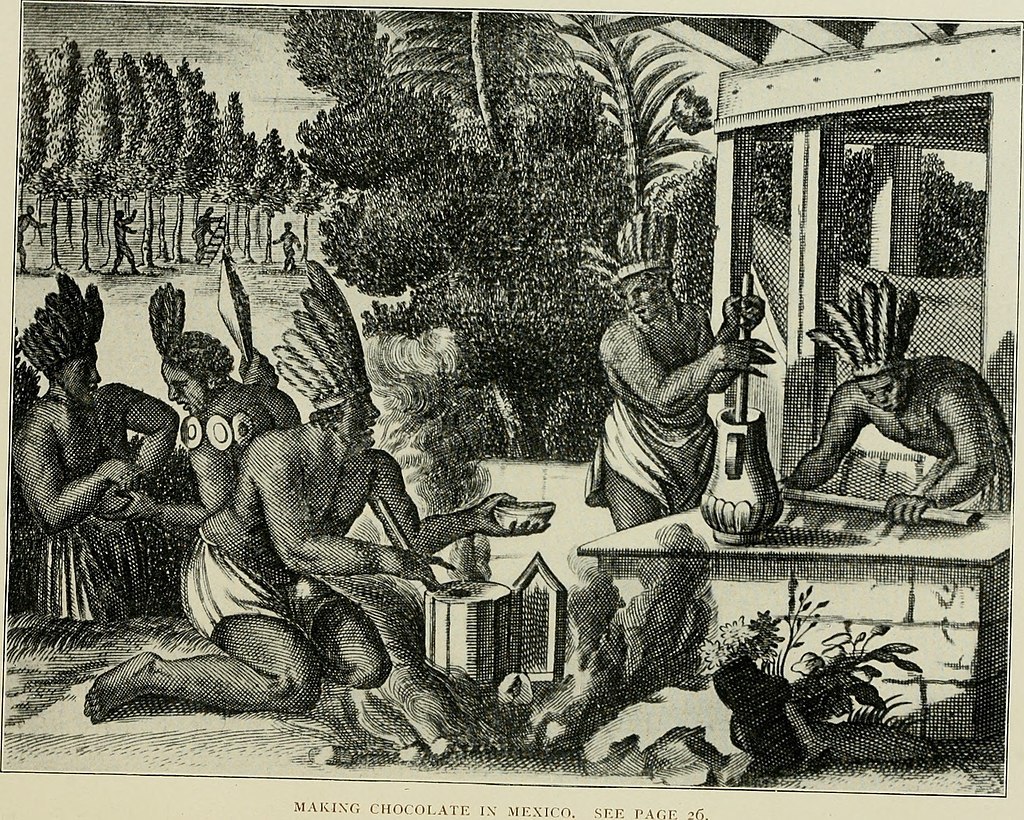

If you are interested in the history of Cacao and how we have come to love chocolate so much, take a look at this article about the cultural history of chocolate.

CACAO BEANS

PARTS USED: Dried seeds and seed shells.

HARVEST: Cacao pods take about 5-6 months to mature. The harvest occurs twice a year, from September to February and May/June, even though there is always ripe and unripe fruit on the same tree.

CONSTITUENTS: Fat, Amino Acids, Alkaloids (Theobromine, Caffeine), Riboflavin, Niacin, Thiamine, Calcium, Iron, Potassium, Magnesium, Vitamins A, C, D and E, polyphenols.

ACTIONS: Diuretic, stimulant, aphrodisiac, anti-depressant, nutritive anti-inflammatory, antioxidant

Crushed Cacao Beans

Image by janiceweirgermia from Pixabay

Diuretic

In Central America, a tea made from crushed Cacao seed shells called ‘nibs’ is used as an effective diuretic. A strong flow of urine is a sign of health and vigour, and any substance that produces this effect is praised as an aphrodisiac, enhancing male potency.

Anti HIV-properties

A pigment extracted from the husks has anti-HIV properties. In vitro studies have demonstrated that polymerized flavonoids present in the husks reduce the damaging effects of HIV. Apparently, they prevent the virus from entering the cells (Unten et al. 1991). But once inside the cell, the virus replicates normally.

Anti-inflammatory

Cacao is incredibly rich in polyphenols, antioxidant flavonoids that have a powerful anti-inflammatory effect.

Animal studies also suggest that Theobromine and Theophylline can ease inflammatory conditions of the respiratory tract, such as asthma, by dilating the lungs and thus helping to relax the air passages.

But unfortunately, most of them are lost due to the standard methods used to process Cacao Beans.

Cardio-Vascular support

Apparently, eating chocolate can be good for your heart health! In 2015, a study found that habitual chocolate consumption can reduce the risk of cardiovascular health issues, providing it is of high quality with a high cacao content. (2)

Cacao can relax and widen the arteries, thus reducing blood pressure and improving blood circulation. Combined with its ability to reduce ‘bad’ cholesterol, it can help prevent heart attacks and strokes.

Skincare from within

The Cacao phenols are also good for the skin. They improve blood circulation to the peripheral cells and improve the smoothness of the skin by helping to hydrate it from within. Long-term use is also said to protect the skin from the harmful effects of the sun.

Mood enhancing

The higher the Cacao content, the better it is for your well-being. Have you ever wondered why you are craving chocolate when doing demanding mental work? It’s your body telling you what it needs: High Cocoa chocolate (min. 65%) has nutritional and stimulating properties that make it a good ‘pick-me-up’.

The flavonols in Cacao improve mood, alleviate symptoms of depression and reduce stress. One study of pregnant women even showed this stress-reducing effect to be conferred to the babies. It is also popular as comfort food to soothe PMS symptoms. Another study showed that older men can benefit from the regular consumption of high Cacao content chocolate, reporting improved health and well-being.

Cognition

Even better, high Cacao content chocolate improves cognitive functions by increasing the blood flow to the brain. The beneficial flavanols can also cross the blood-brain barrier and directly benefit the neurons. For those suffering from cognitive impairments or neuronal conditions such as Alzheimer’s, or Parkinson’s, high Cacao content chocolate is brain food.

The findings are promising, suggesting that more research is warranted.

Blood-sugar regulation

High Cacao chocolate can even have a positive effect on Type 2 Diabetes symptoms. The unexpected findings showed that flavanols can slow the carbohydrate metabolism and uptake in the gut, while stimulating insulin secretion, lowering inflammation and aiding the transfer of sugar from the blood to the muscles.

Weight loss

Interestingly, high cocoa content chocolate actually has a positive effect on the body mass index (BMI). Chocolate eaters (min 81% cocoa) lose weight faster than people who do not eat chocolate.

Anti-Cancer

Several animal studies indicate that a flavanol-rich Cacao diet lowers the risk of cancer – especially breast, pancreatic, liver and colon cancer and leukaemia. However, more research is needed.

Immune system stimulation

Another counterintuitive finding is that Cacao contains antibacterial, anti-enzymatic and immune-stimulating compounds that can have a beneficial effect on oral health.

NOTE

It must be stressed, that all of these benefits only apply to high cocoa content chocolate that is very low in sugar, or without sugar. The common candy bar has NO health benefits. On the contrary, chocolate candy can be harmful.

(In case you are confused about flavonoids, flavanols and flavanols, they are actually different compounds. Take a look at this article to help clear up the confusion.)

References:

(1) Unten, S., H. Ushijima, H. Shimizu, H. Tsuchie, T. Kitamura, N. Moritome, and H. Sakagami. 1991. Effect of cacao husk extract on human immunodeficiency virus infection. Letters Appl. Microbiol. 14:251-254.

(2) (Kwok CS, Boekholdt SM, Lentjes MA, Loke YK, Luben RN, Yeong JK, Wareham NJ, Myint PK, Khaw KT. Habitual chocolate consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease among healthy men and women. Heart. 2015 Aug;101(16):1279-87. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307050. Epub 2015 Jun 15. Erratum in: Heart. 2018 Mar;104(6):532. PMID: 26076934; PMCID: PMC6284792.)

#Ads

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases on Amazon and other affiliate sites.

My interest was piqued when I first spotted this really weird looking-mushroom on one of my local mushroom forays. I had never seen anything like it! A whitish-cream colored, shaggy-looking thing that reminded me of a coral, or a miniature cascading stalactite, or a mop. But certainly not of a mushroom. It grew in clumps, each seemingly flowing into the next. I was instantly smitten.

My interest was piqued when I first spotted this really weird looking-mushroom on one of my local mushroom forays. I had never seen anything like it! A whitish-cream colored, shaggy-looking thing that reminded me of a coral, or a miniature cascading stalactite, or a mop. But certainly not of a mushroom. It grew in clumps, each seemingly flowing into the next. I was instantly smitten.

A couple of thousand years ago, Yews were common throughout Europe and Britain. But they are slow-growing trees that were decimated for the sake of war. Yews were the primary source-wood for longbows – which, before the invention of gunpowder, were the most common weapon of war. Even today, Yew bows are used for making longbows for archery. In medieval times, Yews were planted in and around castle grounds to ensure a steady supply.

A couple of thousand years ago, Yews were common throughout Europe and Britain. But they are slow-growing trees that were decimated for the sake of war. Yews were the primary source-wood for longbows – which, before the invention of gunpowder, were the most common weapon of war. Even today, Yew bows are used for making longbows for archery. In medieval times, Yews were planted in and around castle grounds to ensure a steady supply.