How to Make Natural Body-Care Products?

This article offers a short introduction to how to make natural homemade cosmetics.

Homemade natural cosmetics are a real treat and easy to make

I don’t know about you, but I always like to give at least some homemade gifts at Christmas, so right around now, I start to scratch my head, wondering what to make.

There are plenty of items that are always well-received: jam, syrups, and pickles among them. But I am a bit more ambitious than that. I look for something a bit more special. Homemade body-care products make great gifts that can easily be personalized, and many are straightforward to make without the need for complicated procedures or ingredients.

The best natural cosmetics are homemade using high-quality vegetable oils and butter such as coconut, avocado or almond oil. These can be combined with organic flower waters (hydrosols) and essential oils to make nourishing lotions and crèmes.

Since many natural oils are rich in unsaturated essential fatty acids, it is generally a good idea to make smaller batches to prevent spoilage. What’s so great about natural cosmetics is that you can tailor-make them to specific needs, and there is such a variety of products you can make. Therefore, before you start, consider what kind of product you want to make and what properties it should have.

Emulsifying agents

Lotions and crèmes aim to nourish and moisturize the skin, or even to heal or repair skin damage. They usually consist of an oily and a watery component, such as a hydrosol or tincture. But since water and oil do not mix well

an emulsifying agent is needed to blend them.

Just like oils, emulsifiers also have different properties, and one can’t simply be substituted for another.

Most emulsifying substances are the product of complicated chemical processing, even if they derive from natural materials.

In the past, spermaceti, a substance produced in the heads of whales, was the most common natural emulsifier. Thankfully, nowadays, there are non-animal source alternatives.

Pick your ingredients according to your specific nutritional or therapeutic requirements (see the previous article about oils).

Some oils are ‘drying’ while others are moisturizing. Combining these with humectants such as vegetable glycerine or aloe Vera gel changes the consistency and skin-care benefits. The trick, when blending crèmes, is to combine them slowly have all ingredients at a similar temperature to avoid curdling. If you have ever made mayonnaise from scratch, you have a good idea of what it takes to make a lotion or crème.

Apart from the emulsifying wax, which blends the watery and oily components, you may also need a stabilizer, such as stearic acid. These are added in tiny quantities to stabilize your crème’s consistency. However, use sparingly, or your crème will become chalky instead of smooth.

If you don’t want to mess with oils and waxes, there are now ready-made base crèmes on the market. These generic crème bases can be enhanced by adding special ingredients such as essential oils, infused oils or Aloe Vera gel. However, they can only absorb a few additional ingredients, before they become unstable, so experiment carefully. The quality of such crème bases varies widely, and most contain preservatives or alcohol to increase their shelf-life. However, these chemicals are not that great for the skin, so read the ingredients label carefully, and do your research. Making your own is definitely preferable and will be of much higher quality. For personal use, making small batches is much the best strategy, as you don’t have to worry too much about the shelf-life.

Recipes:

I’d like to share my favourite body butter recipe with you. It is so easy to make and very adaptable to your needs.

Ingredients:

- 100g Shea butter

- 100g Coconut butter

- 100g Cocoa butter

- 100 ml Almond oil

Method:

In a double boiler, melt all the hard ingredients and add the Almond oil at the end. Stir well and let it cool down. This takes a while. Once it starts to set, whip with an electric blender to make it fluffy and creamy. Allow to cool some more and then whip it again. When the consistency is to your liking, fill it in your prepared (sterilized) jars with the help of a spatula.

This is quite a dry, yet very soothing body butter that is generally well tolerated. It is very easily and quickly absorbed by the skin. If you like it a bit richer, you

can adjust the oil or the butter. Cocoa butter and shea butter are great because they stabilize this blend. Coconut oil by itself would be less useful as the melting point is too low, and the butter would only stay solid if kept in a cool or cold place.

You can add a few drops of essential oil in at the end but research the oil first to make sure it is not allergenic or irritating to the skin. Also, keep the percentage of essential oil well low (1-3%)

For an additional therapeutic benefit, add in a small amount of nutritive oil, such as Evening Primrose, Hemp, or Borage Seed oil. (10% of the total amount).

Instead of the plain base oil, you can also use infused oils, such as Calendula, or St. John’s Wort oil for their extra healing qualities.

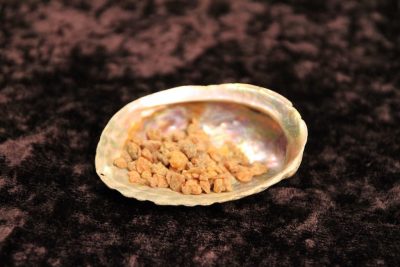

Bath Salts

The cheapest and easiest bath salts are coarse salts, such as Epsom or Sea Salt. Crush to a grainy size (dissolves easier) and add a few drops of a gentle essential oil, such as rose, lavender or Jasmine. Stir and blend well, fill in a jar and let it macerate for a few days. Some people like to add food colouring to make it look more like commercial bath salts, but this is purely for looks. If you don’t mind ‘bits’ floating in your bathtub, you can add a handful of fresh fragrant rose petals or lavender flowers to the salt blend. The salt will dehydrate them and absorb their scent.

Bath Oil

Soaking in water for any length of time dehydrates the skin. Normally, the skin’s natural oil secretions prevent it from drying out, but frequent bathing washes our natural protective layer off. Body butter or simple oil application (almond or apricot oil) replenish the natural skin oils. But better still, use bath oil instead of commercial detergent. Almond or light coconut oil are good choices. Add some drops of essential oil for a beautiful scent (make sure they are not toxic or irritant and don’t overdo it). Add a small amount of Turkey Red Oil, to facilitate the dispersion.

If you don’t like the greasiness of bath oils, but still want to use essential oils in your bath, use plain milk, buttermilk, or cream as a dispersing agent for your essential oils. A tiny blob of honey mixed in is also very pleasant and softens the skin.