Nature Notes:

Samhain

At Samhain, the Goddess retreats into the deep vault of the earth to join her dark lover in the Underworld. Life withdraws, and the landscape turns bleak, cold, and grey. The last fruits, nuts and berries still hang in the bushes, but most are gone. Few flowers withstand the season’s call until the frost kills them off. The birds have left on their journey to the south.

It is a melancholy time, but also a time to turn inward.

We mark this season by remembering those who have gone before us. Death is but a stage of the wheel of life. Far below the surface, the Goddess sheds her wilted gown. Throughout the winter months, she remains in deep meditation as she regenerates her vitality.

We face the cold and darkness as the Sun’s power wanes. Few of its rays can still warm us, and the days grow shorter.

Life and death are aspects of the same eternal cycle. There is no light without darkness, no life without death. Use this time to reflect and remember, to cherish the good and to let go of all that is worn and that wears you down. Concentrate your inner strength in contemplation – for soon, the wheel of the year will turn, and the Sun will be reborn.

Current issue

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Plant Profile:

History of the Cocoa Tree- Theobroma cacao

Plant Profile: Cocoa (Theobroma cacao)

Surely, everybody loves chocolate. Yet, little is known about its origin or its fascinating history. This article is a short introduction to one of my favourite plants: Cocoa – Theobroma cacao, the food of the gods.

Description

If you saw a Cacao tree, you’d never think that this is the stuff that chocolate is made of. As tropical trees go, Cacao is of modest size and height. It only grows to about 10 m to 20 m high. That’s because it is a shade-tolerant ‘understorey tree’. On plantations, where most of them are grown, they are kept much smaller to facilitate easy harvesting.

Cacao trees take about five years to mature and produce fruit, and they can live for over 200 years. But, for commercial purposes, they are considered productive for only about twenty-five years.

The Theobroma genus comprises about 20 species, of which T. cacao is the most widely cultivated one.

Its appearance is very distinctive:

Botanical name: Theobroma cacao

Family: Sterculiaceae

Synonyms:

Coco, Cocoa, Chocolate, Cacahuatl, Tlapalcacauatl, Cacauaxochitle (T. augustifolium)

Origin:

Northern parts of South America and Central America

Distribution:

Humid tropics, most notably Central and South America, West Africa and Sri Lanka, Indonesia and the Philippines

Forest & Kim Starr CC BY 3.0 US , via Wikimedia Commons

Leaves

The mature leaves are dark green, large and glossy, very much in contrast to young leaves that are reddish and seem to droop from the end of the branches. They are pretending to be old and not worth munching on. As they mature, they turn dark green and robust.

Although deciduous, Cacao never sheds all its leaves at once. Young and mature leaves grow side-by-side on the same tree. The greyish-brown bark is rough and covered with patches of different coloured lichen and fungi.

Flowers

But what is most surprising about the Cacao tree are its flowers that sprout in clusters directly from the tree trunk and older branches.

Botanically, this is known as a ‘cauliflorous‘ flower formation. The tiny creamy-pinkish flowers are short-lived and last only for a day, and they are fertile only from sunrise and sunset. If they are not pollinated within that time, they will wither and die.

Cacao is ‘self-incompatible’, meaning it cannot pollinate itself. Nor does the wind help with the task. The pollen is too heavy and sticky for the wind to carry. The task falls to various species of tiny insects.

Fruit

From those tiny dangling flowers grow the most weird-looking pods, oblong and tapered at both ends, somewhat resembling a kind of squash.

The pods come in all colours and sizes and can be ribbed with thick skin, or smooth and thin-skinned, depending on the variety. Some pods only grow to about 4 inches long, but some types develop pods that can reach a whopping 12 inches. The immature fruits are green, turning yellow, orange, red or purple as they mature, a process that can take up to five or six months.

Each pod contains between 20 and 60 smooth, white seeds. As long as the pod stays intact, the seeds remain viable, but once opened and the pulp is removed, they dry out and lose their ability to germinate.

Cacao pods are a favourite monkey food. They may be unfamiliar with chocolate, but they are crazy about the delicious sweet and sour fruit pulp that envelopes the seeds.

Distribution

Cacao is grown in the tropics, but it is very fussy about its growing conditions. The greatest number of wild varieties are found in the lowland rainforest of northern South America, where Cacao is native. A true lowland rainforest species (never found above 100 ft above sea level), it likes to grow near water, e.g. on river banks or seasonally inundated ground.

Cacao likes it hot and steamy: its distribution range is tightly limited to about 15 degrees of latitude on either side of the equator.

Habitat and Ecology

Cacao is a tree of the tropics and very fussy about its growing conditions. Most wild varieties are found in the lowland rainforest of northern South America, where Cacao is native. A true lowland rainforest species (never found above 100 ft above sea level), it likes to grow near water, e.g. on river banks or seasonally inundated ground.

Cacao likes it hot and steamy: its distribution range is tightly limited to about 15 degrees of latitude on either side of the equator.

Cacao needs the shade of taller trees to protect young saplings and their sensitive immature leaves from direct sunlight. High humidity is a necessary prerequisite for healthy growth. But when trees are cut to create plantations, local weather patterns change. It gets drier, which negatively impacts yields and dries out the soil. Climate change also makes the trees more vulnerable to fungi and diseases.

Cacao plays an integral role in rainforest ecology. In natural conditions, it develops a taproot that helps to stabilize the river banks where it prefers to grow. The fruit pulp is a delicacy for many rainforest animals, but monkeys and birds are particularly keen on it.

The History of Cocoa

The native people of Central and South America revered the Cacao tree. They had cultivated Cacao trees for several hundred years before the Conquistadores’ invasion.

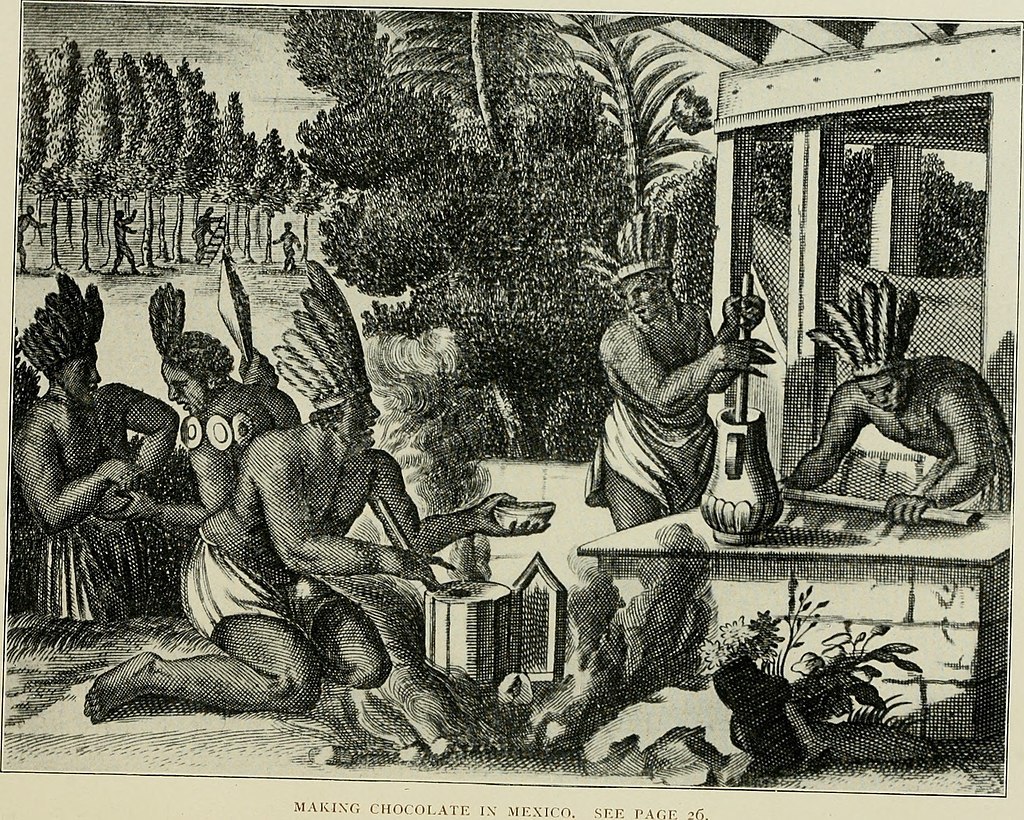

The Aztecs cultivated several species of cacao, none of which are grown commercially today. They used different species for distinct purposes: The types with the largest seeds were used as currency (money does grow on trees ;-). But it was the species with the smallest seeds, ‘Tlacacahuatl’, which was used to make a sacred beverage called Xocoatl.

Cocoa as privilege

Drinking Xocoatl was the privilege of nobles and priests, who consumed it in vast quantities. Moctezuma, the last Aztec emperor, devoured fifty golden goblets daily. This beverage was very different to what we now know and love as drinking chocolate. The Aztec version was savoury, not sweet, and there were many ways to prepare it depending on the occasion.

For general use, roasted Cacao seeds were ground and mixed with Atole (coarse, roasted corn flour) and whisked into a rich foaming brew. Chillies, Vanilla, Cinnamon and salt were added to taste.

Ceremonial use of Cocoa

The ceremonial beverage, Xocoatl, was considered as sacred as other psychotropic ritual plants, such as Ololuiqui (Turbina corymbosa) or sacred mushrooms (Psilocybe sp.). The Spanish chronicler Sahagún reports that Cacao, ‘…especially that made with the green, young fruits, has the power to intoxicate, to make one dizzy and to make one drunk…’ He warned against drinking too much of it but says, consumed in moderation, it fortifies the body and spirit.

Cocoa as an Aphrodisiac

Xocoatl was a powerful aphrodisiac and stimulating tonic. Moctezuma regularly fortified himself with it before entering the royal harem. The Mixtec, contemporaries of the Aztec, who inhabited the Oaxacan plateau, used Xocoatl in their marriage ceremonies. Chocolate has not lost its aphrodisiac appeal, even now. Chocolate probably ranks as the most popular choice for a romantic gift, next to flowers.

Neurochemical research

Neurochemical research has been able to shed some light on this ancient reputation. Scientists at the Neurosciences Institute in San Diego found three compounds in dark chocolate that closely resemble a naturally occurring neurotransmitter known as ‘Anandamide’.

Anandamide, (from Sanskrit Ananda = bliss), links to THC receptor sites in the brain. They produce a similar but less pronounced sense of well-being as Tetrahydrocannabinol, found in Cannabis. The scientists also found compounds (N-acylethanolamines) that block the breakdown of Anandamide [Piomelli, 1996].

Anandamide is the primary neurotransmitter present in the uterus during the early stages of pregnancy. It seems like its role is to convey a sense of bliss and contentment to welcome the embryonic spirit into the womb. Chocolate is also rich in Phenylethylamine, the signature compound associated with the euphoric state of being in love.

Mistaken identity and its consequences

When Cortés and his men arrived at the shores of the new world, Moctezuma mistook them for ambassadors of the feathered serpent god, Quetzalcoatl. He welcomed them with many fine gifts, including gold, jewellery and precious stones.

Appropriate to the occasion of welcoming divine guests, he also honoured them with a cup of the sacred Xocoatl brew, served in golden goblets. But the Spaniards were more interested in the gold and silver than in the cocoa brew, which they deemed ‘more suitable for hogs than men’. It took many years, but eventually, cocoa grew on them.

From Xocolatl to chocolate

Much experimentation and modification of the original recipe eventually produced something suitable for the Hispanic palate. And it soon became a hit.

Credit for it must be given to an order of Spanish nuns who lived in the province of Chiapas in southern Mexico. They learned to roast the cocoa beans, like the Aztecs, but instead of adding chilli and salt, they mixed them with cane sugar, vanilla and cinnamon.

The nuns loved their chocolate drink so much that they refused to abstain from it, even during mass.

Aware of Cacao’s aphrodisiac reputation, the Bishop was alarmed and tried to suppress the new custom. But, the nuns protested, insisting that the chocolate drink helped them overcome ‘the weakness of the stomach’ and even aided their efforts to pray. The Bishop gave in, and the nuns were granted permission to continue their unorthodox ways. And this is how the reformed Xocolatl conquered the world.

Cocoa conquers the Old World

When Cortés returned to Spain, among the many wondrous things he brought back was a sack of Cacao beans along with the recipe for the novel beverage. As in the New World, chocolate was, at first, reserved for the nobility. No ordinary mortal could afford its astronomical price. But it became an immediate hit at all the Royal Courts of Europe.

Cunningly, the Spaniards managed to keep the recipe a secret for almost a century. They had begun to plant Cacao plantations in their New World colonies soon after conquering the Aztec Empire, securing their absolute control of the cocoa trade. But ultimately, the secret of the cocoa bean got out, and their monopoly was broken. Other colonial powers established plantations far from the Theobroma’s original homeland – first in Indonesia and the Philippines, and later in West Africa and South America.

Today, Cacao is one of the most significant cash crops for small scale farmers in developing countries. It is worth about $9.5 billion in world trade. Worldwide, more than 4 million tons of Cacao beans are produced annually, more than half of which are grown in West Africa.

Hot Chocolate – a drink of the Avant-Garde

By the middle of the 17th century, ‘chocolate houses’ began to appear, rivalling ‘coffee houses’, as meeting places of the Avant-Garde. By the end of the 17th century, hot chocolate had become so popular that the government thought it worthwhile to impose a tax on it!

When the Dutch Cacao producer, Van Houten, invented a new processing method in 1828, drinking chocolate became even more popular. Unprocessed Cacao beans contain up to 53% of fat, making them hard to digest. Van Houten used a hydraulic press to squeeze out the fat content of Cocoa powder, reducing it to 10–13%. The new, lighter chocolate powder proved even more popular. Better still, the cacao butter was not wasted, but was used to improve the consistency of solid chocolate bars.

From Cocoa to Chocolate

Solid chocolates also became ever more popular. They were transformed by an innovation introduced by a Swiss chocolate manufacturer, who came up with the simple, but brilliant idea of adding condensed milk to the cocoa butter blend. This creates the familiar creamy texture of milk chocolate. Today, milk chocolate has become the most popular type of chocolate product, and the Swiss are the world leaders in this category. And, they are also world leaders in consumption, with an annual equivalent of 5.5 kg of cocoa beans per capita.

During much of the 19th century, chocolate enjoyed the status of a magical panacea. It was believed to cure just about any ailment. This notion seems a little exaggerated, but Cacao does have some interesting medicinal properties. We will explore these in next week’s post.

Further resources:

International Cocoa organization icco

International Fairtrade / Cocoa

And if you are looking for some delicious AND ethical chocolate, check out my friend Jennifer’s Sombra Buena chocolate.

#Ads

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases on Amazon and other affiliate sites.

More articles:

What to sow in January

If you are itching to get going with the gardening year, you’ll be wondering what you could possibly sow in January. There are – but only under glass.

Topiaria gaudium fever

There is a strange fever going around. It only affects gardeners. I call it ‘Topiaria Gaudium Fever’, a strange condition marked by extreme excitement caused by the start of the new gardening season.

The Signs of the Times

Today is a big day, in Astrology. While Astrology is not normally my topic here, I feel compelled to talk about it. We have all noticed the build-up of political tensions in the last 2-3 years. There have been outbreaks of political uprisings everywhere, from Hong...

What is the use of New Year’s intentions?

Although New Year’s is just a date on the calendar, it does represent a threshold. It marks a time at which we can reflect and re-orientate ourselves . It is a time of ‘en-visoning’ the future, and our future self.

Let them eat…beans?

Beans are rich in proteins and are a great meat replacement for a plant-based diet. But that is not all. They also have medicinal uses. Mucuna pruriens is especially interesting

Blackberries (Rubus fruticosus)

Autumn equinox always arrives with a shock: summer is over, winter is on the approach! How can that be? It seems only such a short while ago that we laughed and played in the summer sun! But all too soon I hear the equinox winds hurling outside my window and watch...

Apple Tree

Description: The Apple Tree is one of the most anciently cultivated fruits of Eurasia. It is believed to have developed in central Asia, where the greatest genetic variation occurs in the wild. In cultivation, trees are usually trained and do not reach more than...

Annatto (Bixa orellana)

Description: Annatto, or Achiote, as it is commonly called in Latin American countries, is a tropical shrub that can grow up to about 20 meters high. The pinkish-white flowers develop into a bright red, heart-shaped and exceedingly bristly fruit, which is inedible....

Aloe (Aloe vera)

Although originating in the hot and arid climes of northern Africa, to most of us Aloe Vera is no longer an exotic stranger. Not only do we see it advertised as a popular ingredient in a multitude of household products, ranging from washing-up liquid to latex gloves,...

Acorns

I don't know why I have been ignoring acorns all this time. But this year, out of nowhere, it suddenly struck me that I should give them a try. Oaks are quite plentiful in my region and thus acorns are not in short supply. And so, I unexpectedly found myself filling...

Açai (Euterpe oleracea)

Description: A slender, graceful palm of the Arecaceae family, Açai is native to the seasonally inundated lowland forests of eastern South America, especially Brazil. Several stems sprout from its base and it can grow to about 15-25m high. It takes 4-5 years to...